Elizabeth Moss as Offred in season three of The Handmaid’s Tale. Channel 4

Elizabeth Moss as Offred in season three of The Handmaid’s Tale. Channel 4

The ongoing TV adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale has done much to remind us of the astonishing pertinence of Margaret Atwood’s novel – which was first published in 1985 and is soon to be followed by a sequel: The Testaments. In particular, it has brought the costume of the handmaids, carefully described by Atwood in the book, to the attention of a new generation of thinkers.

In the novel, the red cloak and dress, worn with a white bonnet, are together described as a “modesty costume”. In Gilead – the repressive American regime in which the main protagonist Offred is forced to live – it is intended to function as a sign of female subservience.

But, as the #resistsister hashtag chosen by production house HULU to market the series suggests, the “modesty costume” – despite its intended function as a symbol of subservience – has remarkable potency when removed from its Gileadean context and redeployed as a symbol of female agency and the defiance of oppression. And this is exactly how the costume has functioned in recent years, when worn by women protesting the insidious erasure of female rights in the West.

In 2017, handmaids marched on Capitol Hill, Washington, in protest at the Republican healthcare bill which was seen to threaten women’s bodily autonomy. And in the same year, handmaids entered the Texas senate house to protest abortion-related legislation. Meanwhile, protesters against Trump’s 2018 and 2019 visits to the UK also sported handmaid costumes.

Beyond the UK and America, the modesty costume has also been co-opted as a symbol of female agency and protest – in countries including Poland, Argentina and Croatia. Like Offred, the protesting handmaids of recent years also refuse to be objectified – their bodies are their own and signify what and how they want them to signify.

In the introduction to the 2017 UK edition of The Handmaid’s Tale, Atwood tells us that “modesty costumes worn by the women of Gilead are derived from Western religious iconography”. This grounding of the costumes in the traditions of the church again brings them closer to the realms of non-fiction. And it reminds us that, over the centuries, countless women in the Christian West have been defined by appearance or attire and have been variously objectified by those in authority over them.

Shut away

Among these countless women, there is a particular group called “anchorites” (anchorites could be men, but were more frequently women). Anchorites, who were very common in England in the Middle Ages, were people who wanted to live lives of Christian prayer and extreme devotion to God. In order to do this, they allowed themselves to be permanently enclosed in small rooms (called “cells”) adjoining their local church and vowed themselves to a life of chastity and penance. Their enclosure began when they were literally bricked into their cells, and was meant to continue until the moment of their death. In fact, we have quite a few records of anchorites being buried within their own cells.

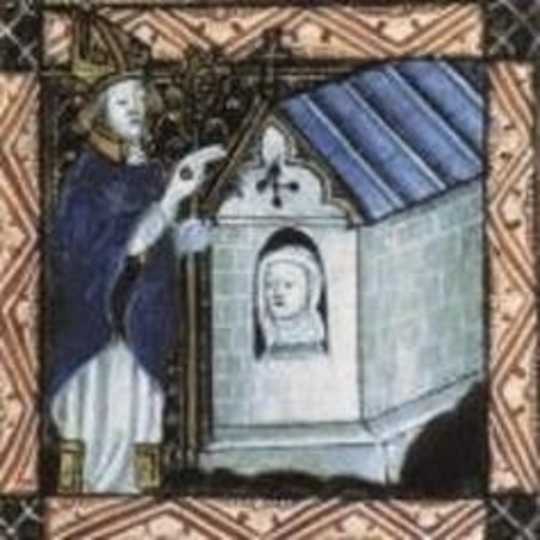

A bishop blesses an anchorite as he encloses her in her cell. Parker Library, courtesy of the Master and Fellows, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, Author provided

A bishop blesses an anchorite as he encloses her in her cell. Parker Library, courtesy of the Master and Fellows, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, Author provided

Of course, there are a lot of differences between Atwood’s fictional handmaids and the historical anchorites. The latter were not, in fact, defined by what they wore – as their enclosure made them more or less invisible to the world, they were not meant to worry too much about their clothes. And neither were they the subjects of a repressive regime – they were not enclosed unless they actively sought it out as a lifestyle (though the issue of their motivation and agency is problematic and would be worth an article on its own).

But there are certainly similarities between the anchorite and the handmaid. Atwood emphasises that the handmaid is meant to live in a state of perpetual fear and so was the anchorite, as suggested by 12th-century theologian Aelred of Rievaulx in his book of guidance, De Institutione Inclusarum:

Beware of your weakness and like the timid dove go often to streams of water where as in a mirror you may see the reflection of the hawk as he hovers overhead and be on your guard.

And, for both women, the body is a site of considerable conflict and anxiety. The Handmaid’s body, in Atwood’s narrative, is a “sacred vessel” – valuable only for its childbearing potential. The anchorite’s body, meanwhile, is of worth only insofar as it houses the “jewel” of virginity – as Aelred wrote:

Bear in mind always what a precious treasure you bear in how fragile a vessel.

Objectification

But what is intended as oppression in Gilead does not inevitably function thus. Aunt Lydia wanted the handmaids to be “pearls”, but Offred resisted this. The modesty costumes were meant to indicate subservience, but they have been redeployed by activists to mean the opposite.

Is it, then, equally possible that the medieval anchorite took her apparent objectification and turned it into an opportunity to assert her own agency? We might perceive the anchorite only partially (her head, isolated at the window of her cell, as in the medieval image above), but she perceives herself fully. We might see only her enclosure, but she perceives herself as “a bird of heaven” (according to a 13th-century English book of guidance for anchorites – Ancrene Wisse), soaring at liberty in her vivid, independent imagination.

So, while the lives of the fictional handmaid and the real anchorite are not the same, they have in common their isolation from the world around them and their submission (whether enforced or chosen) to wills other than their own. But they should not be seen as nothing more than passive victims – instead we should credit them both with the capacity to turn subjection into agency and subservience into freedom.![]()

About The Author

Annie Sutherland, Associate Professor; Rosemary Woolf Fellow, Tutor in Old and Middle English, Somerville College, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Books on Inequality from Amazon's Best Sellers list

"Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents"

by Isabel Wilkerson

In this book, Isabel Wilkerson examines the history of caste systems in societies around the world, including in the United States. The book explores the impact of caste on individuals and society, and offers a framework for understanding and addressing inequality.

Click for more info or to order

"The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America"

by Richard Rothstein

In this book, Richard Rothstein explores the history of government policies that created and reinforced racial segregation in the United States. The book examines the impact of these policies on individuals and communities, and offers a call to action for addressing ongoing inequality.

Click for more info or to order

"The Sum of Us: What Racism Costs Everyone and How We Can Prosper Together"

by Heather McGhee

In this book, Heather McGhee explores the economic and social costs of racism, and offers a vision for a more equitable and prosperous society. The book includes stories of individuals and communities who have challenged inequality, as well as practical solutions for creating a more inclusive society.

Click for more info or to order

"The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People's Economy"

by Stephanie Kelton

In this book, Stephanie Kelton challenges conventional ideas about government spending and the national deficit, and offers a new framework for understanding economic policy. The book includes practical solutions for addressing inequality and creating a more equitable economy.

Click for more info or to order

"The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness"

by Michelle Alexander

In this book, Michelle Alexander explores the ways in which the criminal justice system perpetuates racial inequality and discrimination, particularly against Black Americans. The book includes a historical analysis of the system and its impact, as well as a call to action for reform.