NATO military forces

“Your country needs you!” The 1914 poster of Lord Kitchener pointing an accusatory finger at those reluctant to volunteer to fight for the British Army in the first world war is one both copied and parodied even to this day. But calling for volunteers then was not enough.

While hundreds of thousands of British men did, indeed, volunteer to serve in the first flush of jingoistic patriotism in 1914, the manpower well soon began to run dry. Conscription was needed. Men had to be forced to serve. But it took until 1916 before the British government finally took the decision to introduce conscription (or compulsory enlistment) – it knew how politically unpopular it would be.

Forcible conscription has always been something that governments across Europe have been reluctant to introduce. It is not only unpopular among those asked to serve – and their families – but it also takes human capital out of any state’s workforce and has economic implications. Despite this, however, some form of conscription does still exist today in most European countries. But as the implications of Russia’s war against Ukraine come to be better understood, introducing or extending conscription is increasingly being discussed in European Nato states.

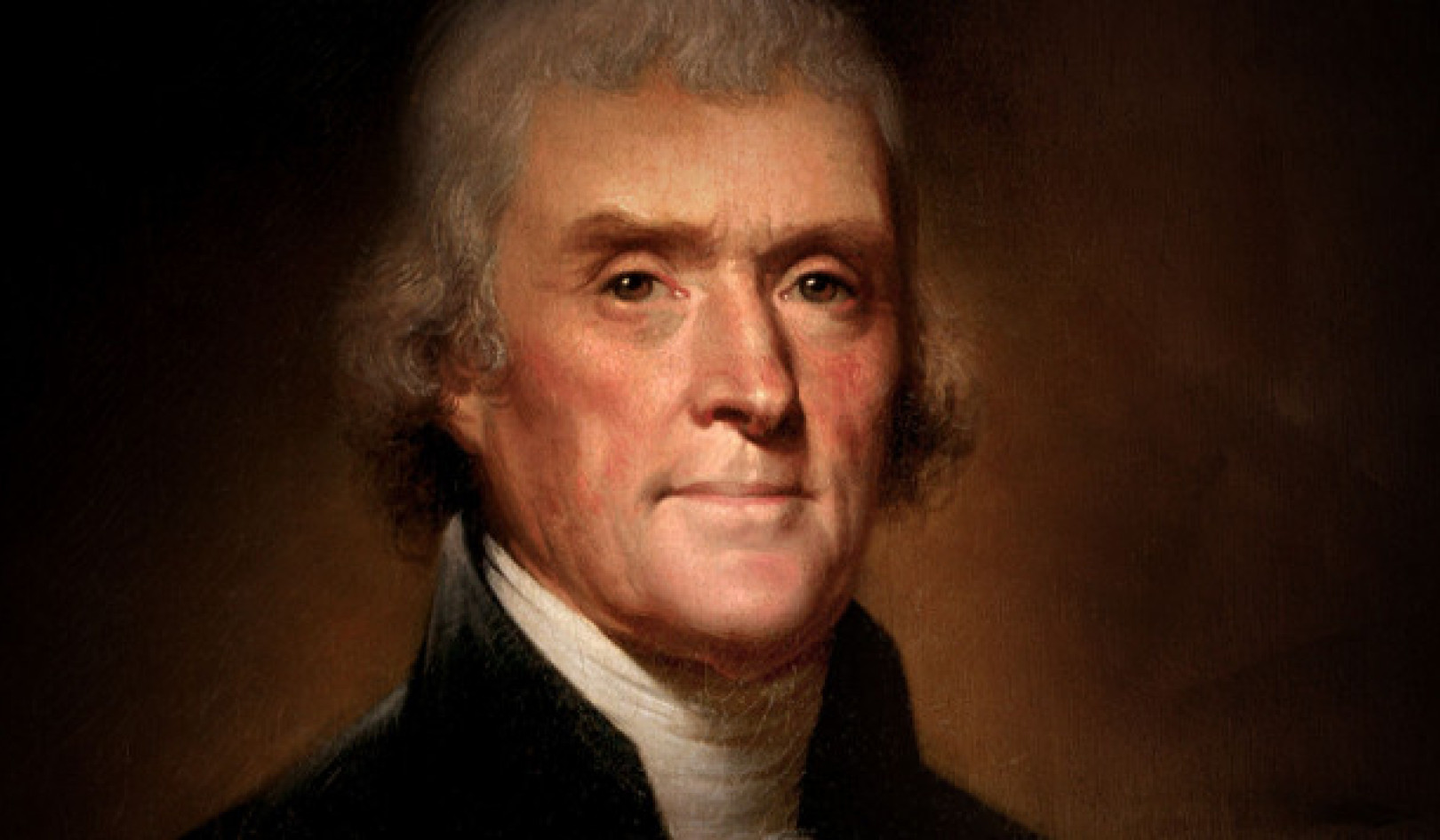

Countries across Europe are considering extended or introducing conscription. Shutterstock

Of the major mainland European Nato powers, France ended conscription (which had been in place since the revolution) in 1996 and Germany did so in 2011. But, over the past few months, political leaders in both countries have been discussing the reintroduction of forms of conscription or national service.

In other countries in Europe, there has traditionally been a type of “conscription-lite” in operation. That is, rather than actual conscription (across a typical cohort of those aged 18-27 and for a usual term of 11 months) it is more a form of draft, where only a percentage of an eligible cohort of young men is actually called to serve. This has been the norm, in particular, across the Nordic and Baltic countries. Today, though, the form of conscription practised in these areas is becoming less “lite”.

Sweden, which joined Nato in March, had dropped conscription in 2010 but reintroduced it in 2018 as the country prepared to join Nato. The government has also now (since January) broadened its national service obligation into something known as the “total defence service”. This means that whereas the previous form of conscription drew in only 4,000 young people out of a potential pool of 400,000 every year, since January this number will need to grow to 100,000 (and will include women). Those called will be asked to perform a civic duty, which could be in the military or, potentially, in the emergency services. It is estimated that 10% of the 100,000 will do so unwillingly.

Finland, the other Nordic country that has recently joined Nato, could hardly expand its conscription net any further. This is a country that has maintained conscription since the second world war and draws in 27,000 male citizens every year (about 80% of the available cohort). The Baltic States, such as Finland, share a border with Russia (or Moscow’s Kaliningrad exclave) and have also recently strengthened their call-up policies.

Latvia reintroduced conscription in January this year, having removed it in 2006. Lithuania had dropped its call-up in 2008 but reintroduced it in 2016 in the wake of the first Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014. Estonia has actually always maintained a form of conscription since independence in 1991, but has recently expanded the net of those liable for call-up.

Conscription extended in Ukraine

Ukraine is now, like Britain back in 1914, running out of soldiers. The country already has conscription for 18-26 year-olds but only those above 27 were actually asked to serve in combat roles (although many volunteers under 27 did as well). This, as the government of Volodymyr Zelensky understands, has to change. To replace those lost in the war and to maintain the ability to rotate troops in and out of the front lines, Ukraine needs a larger pool of military manpower. The over 27s and volunteers were no longer enough.

But casting the manpower net wider is a toxic issue in Ukraine, and as ever, such conscription is not popular. Many Ukrainians consider the system of enlistment to be unjust and beset by corruption. There is a sense that those without money or influence will be those that come to serve in the front lines.

Nevertheless, the situation in Ukraine has demanded change. A draft bill to lower the age of combat service to 25 was put forward in the Ukrainian parliament in December 2023 and it received parliamentary approval in February. Zelensky, expressing reluctance, finally signed the bill into law on April 2.

The toxicity of conscription is also felt in the UK. Here, and unlike most other European states, the notion of conscription has never been accepted. It has always been particularly unpopular. But now, even in the UK, the “c-word” is again beginning to be whispered.

In January, the head of the British Army, Gen Sir Patrick Sanders, called for a “national mobilisation”. He wants to see a “citizen army” created that could be used to augment the regular army. He did not use the emotive word, “conscription”, although others presumed that this was what he was talking about, including the UK government.

Accordingly, government spokespersons moved quickly to quash any notions that conscription was on any agenda. For this is a UK government still acutely conscious of the toxicity of the word. While aware of the need for some sort of national service, it would much rather have a latter-day Kitchener asking merely for volunteers than force anyone to perform any form of national service against their will.![]()

Rod Thornton, Associate Professor/Senior Lecturer in International Studies, Defense and Security., King's College London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.