The purpose of our social, economic and political systems is to enable all Australians to lead good lives. Australia is doing well on some fronts. It ranks third out of 188 countries on the UN Human Development Index, which takes into account life expectancy, education and national income per capita. We also rank 19th on national income per capita.

You might expect that the more equal opportunities in these countries might reduce other differences between the genders, such as what kind of jobs people are more likely to have, or personality traits such as kindness or a tendency for risk-taking.

Why do the richest 1% of Americans take 20% of national income, but the richest 1% of Danes only 6%? Why have affluent British people seen their share of national income double since 1980, while over the same period, the income share of wealthy Dutch hasn’t budged?

- By Sapna Parikh

If the United States doesn’t address rising inequality, the middle class could start feeling the effects in the form of fewer government services, one expert says.

If the United States doesn’t address rising inequality, the middle class could start feeling the effects in the form of fewer government services, one expert says.

Newly released data on life expectancy across the U.S. shows that where we live matters for how long we live. A person in the U.S. can expect to live an average of 78.8 years, according to the most recent numbers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Newly released data on life expectancy across the U.S. shows that where we live matters for how long we live. A person in the U.S. can expect to live an average of 78.8 years, according to the most recent numbers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

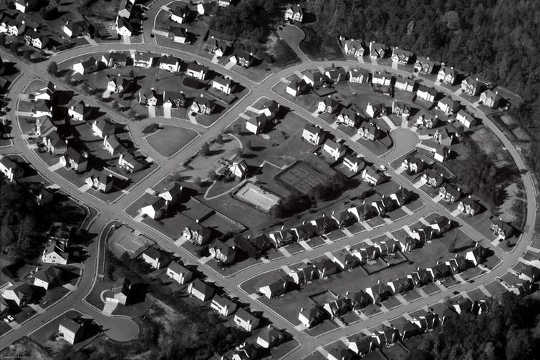

Researchers have created an interactive, map-based tool—the Opportunity Atlas—that can trace the root of people’s outcomes, such as poverty or incarceration, to the neighborhoods in which they grew up.

- By Rob Nicholls

Few things are more annoying than spending a large sum of money on a purchase, only to discover that someone else got the same thing for a lower price. This often happens with airfares. You go the same website, search the same airline, choose the same seat row and fare conditions, but you’re offered a different price depending on when and where you do it. Why?

For millions of American women – both those who’ve survived assault and those who have experienced workplace harassment – seeing a man on the path to promotion despite allegations of harassment is jarring yet painfully familiar.

In the early days of industrial capitalism there were no protections for workers, and industrialists took their profits with little heed to anyone else.

In the early days of industrial capitalism there were no protections for workers, and industrialists took their profits with little heed to anyone else.

- By Stephen Bell

In the last decade or more, economic growth has slowed across the Western world, although a belated though weak recovery has been under way since around 2017.

In the last decade or more, economic growth has slowed across the Western world, although a belated though weak recovery has been under way since around 2017.

Racial wealth inequality was an important factor contributing to the riots in many American cities in the 1960s, but a half-century later, the issue has gotten short shrift, researchers report.

Racial wealth inequality was an important factor contributing to the riots in many American cities in the 1960s, but a half-century later, the issue has gotten short shrift, researchers report.

Buried deep in a note towards the end of a recent bulletin published by the British government’s statistical agency was a startling revelation.

Australia as a nation has never been richer. But it is now also more unequal than at any time since the early 1980s. This inequality takes many forms, not least between suburbs and neighbourhoods. And our research suggests the few celebrated examples of famous Australians who emerged from disadvantaged neighbourhoods are the exceptions to the rule for children who grow up in them.

Australia as a nation has never been richer. But it is now also more unequal than at any time since the early 1980s. This inequality takes many forms, not least between suburbs and neighbourhoods. And our research suggests the few celebrated examples of famous Australians who emerged from disadvantaged neighbourhoods are the exceptions to the rule for children who grow up in them.

- By James Devitt

American workers’ occupational status reflects that of their parents more than previously known, a new study shows.

American workers’ occupational status reflects that of their parents more than previously known, a new study shows.

The findings reaffirm more starkly that the lack of social mobility in the United States is in large part due to the occupation of our parents.

Many Americans deeply believe that people should pull themselves up by their bootstraps. After all, individual responsibility is a core American value. Too much emphasis on an individual’s responsibility, however, may result in overlooking the societal and historically causes that keep racial minorities such as blacks at an economic and health disadvantage.

Scholars of international political economy, such as myself, recognize that trade hasn’t always been good for poorer Americans. However, the economic fundamentals are clear: Tariffs make things worse. Tariffs are a tax on imports. As taxes go up, so do the prices of foreign goods. Unfortunately, protecting a few narrow industries can generate much broader costs. Not least, consumers now have to pay more for everyday goods.

Women comprise 42% of Australia’s homeless population. Not only do many women become homeless due to family violence, homelessness can expose them to further gendered violence. Research shows homeless women experience violence – or feel vulnerable to it – in crisis accommodation, such as private rooming houses and motels, to which housing services often refer them due to the scarcity of more suitable alternatives.

Women comprise 42% of Australia’s homeless population. Not only do many women become homeless due to family violence, homelessness can expose them to further gendered violence. Research shows homeless women experience violence – or feel vulnerable to it – in crisis accommodation, such as private rooming houses and motels, to which housing services often refer them due to the scarcity of more suitable alternatives.

Life expectancy in the UK varies dramatically depending on where you live. As a recent BBC Panorama investigation highlighted, “the rich live longer and the poor die younger”.

Life expectancy in the UK varies dramatically depending on where you live. As a recent BBC Panorama investigation highlighted, “the rich live longer and the poor die younger”.

According to a May 2018 report from the Pew Research Center, since 2000, suburban counties have experienced sharper increases in poverty than urban or rural counties.

An increasing number of people are sleeping outside in tents, doorways, and under bridges. In the United States, 192,875 people were unsheltered on a given night in January 2018, a 9% increase from 2016.

While researching how hard it is for low-income Americans to eat healthy on tight budgets, I’ve often found a mismatch between what people want to eat and the diet they can afford to follow.

Societies tend to become more unequal over time, unless there is concerted pushback. A society that fails to invest in its children, to protect its land and water, or to build a future is courting collapse. The process feeds on itself, growing like a cancer...