The United States International Trade Commission (USITC) recently came out with projections on the economic effects of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade deal. The USITC’s report is the third major study on the TPP from the past two years. The USITC is legally required to provide this report.The USITC report shows that the TPP would have relatively little impact on the volume of trade. This is consistent with the projections from a study by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) (which only examined the impact on agriculture), but is far out of line with the projections by the Peterson Institute for International Economics, the producer of the third major study.

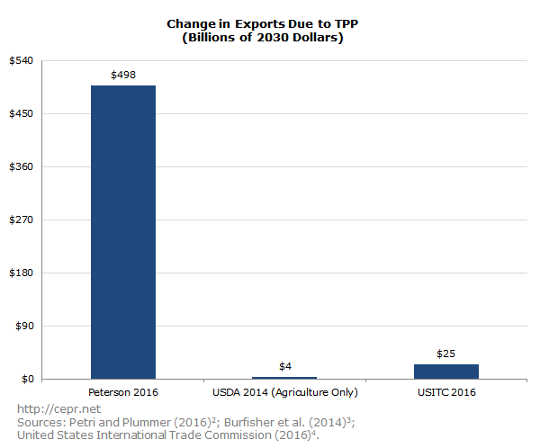

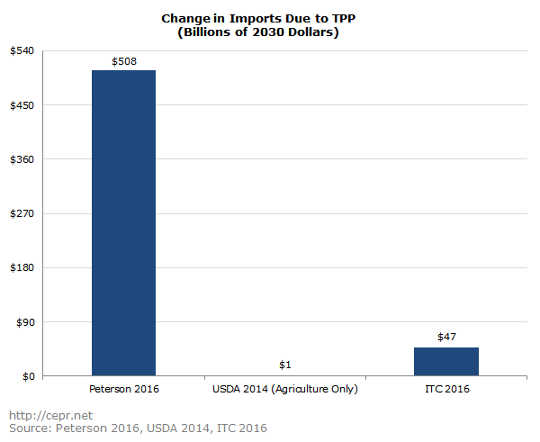

Figure 1 below shows the change in total exports projected in the USITC report and the Peterson Institute study, and the projected increase in agricultural exports from the USDA study.[1]

The USITC study projects that exports will increase by less than 1.0 percent when the effects of the TPP are fully felt in 2032. The USDA study also projects an increase in agricultural exports of less than 1.0 percent. By contrast, the Peterson Institute projects that exports would rise by $498 billion as a result of the TPP, an increase in exports of 9.1 percent against its baseline. This increase is more than an order of magnitude larger than the increase in exports projected by the USITC or the USDA relative to their baselines. (The USDA baseline of course only refers to agricultural exports.)

It is striking that the Peterson Institute projections are so far out of line with those produced by the USITC and the USDA. Clearly it is using assumptions that imply the TPP will have a far larger impact than those used in the other two modeling exercises.

It is striking that the Peterson Institute projections are so far out of line with those produced by the USITC and the USDA. Clearly it is using assumptions that imply the TPP will have a far larger impact than those used in the other two modeling exercises.

[1] All estimates are presented in 2030 dollars (using data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve and projections from the Congressional Budget Office).

[2] Petri, Peter A., and Michael G. Plummer. The Economic Effects of the Trans-Pacific Partnership: New Estimates. Working Paper 16-2. January 2016. Peterson Institute for International Economics.

[3] Burfisher, Mary E., John Dyck, Birgit Meade, Lorraine Mitchell, John Wainio, Steven Zahniser, Shawn Arita, and Jayson Beckman. Agriculture in the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Economic Research Report #176. October 2014. United States Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

[4] United States International Trade Commission. Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement: Likely Impact on the U.S. Economy and on Specific Industry Sectors. Publication Number 4607. May 2016. United States International Trade Commission.

About the Author

Dean Baker is co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, DC. He is frequently cited in economics reporting in major media outlets, including the New York Times, Washington Post, CNN, CNBC, and National Public Radio. He writes a weekly column for the Guardian Unlimited (UK), the Huffington Post, TruthOut, and his blog, Beat the Press, features commentary on economic reporting. His analyses have appeared in many major publications, including the Atlantic Monthly, the Washington Post, the London Financial Times, and the New York Daily News. He received his Ph.D in economics from the University of Michigan.

Dean Baker is co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, DC. He is frequently cited in economics reporting in major media outlets, including the New York Times, Washington Post, CNN, CNBC, and National Public Radio. He writes a weekly column for the Guardian Unlimited (UK), the Huffington Post, TruthOut, and his blog, Beat the Press, features commentary on economic reporting. His analyses have appeared in many major publications, including the Atlantic Monthly, the Washington Post, the London Financial Times, and the New York Daily News. He received his Ph.D in economics from the University of Michigan.

Recommended Books

Getting Back to Full Employment: A Better Bargain for Working People

by Jared Bernstein and Dean Baker.

This book is a follow-up to a book written a decade ago by the authors, The Benefits of Full Employment (Economic Policy Institute, 2003). It builds on the evidence presented in that book, showing that real wage growth for workers in the bottom half of the income scale is highly dependent on the overall rate of unemployment. In the late 1990s, when the United States saw its first sustained period of low unemployment in more than a quarter century, workers at the middle and bottom of the wage distribution were able to secure substantial gains in real wages.

This book is a follow-up to a book written a decade ago by the authors, The Benefits of Full Employment (Economic Policy Institute, 2003). It builds on the evidence presented in that book, showing that real wage growth for workers in the bottom half of the income scale is highly dependent on the overall rate of unemployment. In the late 1990s, when the United States saw its first sustained period of low unemployment in more than a quarter century, workers at the middle and bottom of the wage distribution were able to secure substantial gains in real wages.

Click here for more info and/or to order this book on Amazon.

The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive

by Dean Baker.

Progressives need a fundamentally new approach to politics. They have been losing not just because conservatives have so much more money and power, but also because they have accepted the conservatives' framing of political debates. They have accepted a framing where conservatives want market outcomes whereas liberals want the government to intervene to bring about outcomes that they consider fair. This puts liberals in the position of seeming to want to tax the winners to help the losers. This "loser liberalism" is bad policy and horrible politics. Progressives would be better off fighting battles over the structure of markets so that they don't redistribute income upward. This book describes some of the key areas where progressives can focus their efforts in restructuring the market so that more income flows to the bulk of the working population rather than just a small elite.

Progressives need a fundamentally new approach to politics. They have been losing not just because conservatives have so much more money and power, but also because they have accepted the conservatives' framing of political debates. They have accepted a framing where conservatives want market outcomes whereas liberals want the government to intervene to bring about outcomes that they consider fair. This puts liberals in the position of seeming to want to tax the winners to help the losers. This "loser liberalism" is bad policy and horrible politics. Progressives would be better off fighting battles over the structure of markets so that they don't redistribute income upward. This book describes some of the key areas where progressives can focus their efforts in restructuring the market so that more income flows to the bulk of the working population rather than just a small elite.

Click here for more info and/or to order this book on Amazon.

*These books are also available in digital format for "free" on Dean Baker's website, Beat the Press. Yea!