Sarkao/Shutterstock.com

Sarkao/Shutterstock.com

A number of years ago, I found myself at a public sex beach in southern France for research purposes. Unsurprisingly, I experienced some ethical dilemmas. Because I was researching the ethics of sexuality, my research involved potentially having sex with men and women at the beach.

The question of whether I “should” or “could” do so was complicated by a number of factors. I am a woman. I am queer. I am an academic. At the time, I was also in an (increasingly) difficult relationship with a man who was a philosopher. Given all of these complex factors, I desperately needed ethical assistance supported by philosophy (that I read and revered) that did not judge, and was aligned to my sexuality. But this philosophy – whichever way I turned to find it – doesn’t exist.

Ethics is a field of philosophy that seeks out the foundations of how we should live our lives. It seeks to provide a framework for doing the “right” thing. This framework is founded on conventional Western philosophical ideas. For instance, conventional ethical thinking finds homosexuality to be an “issue”, rather than an inherent characteristic of bodies. The ethical theorist John Finnis, for example, recently argued that the ethics of homosexuality are still up for discussion.

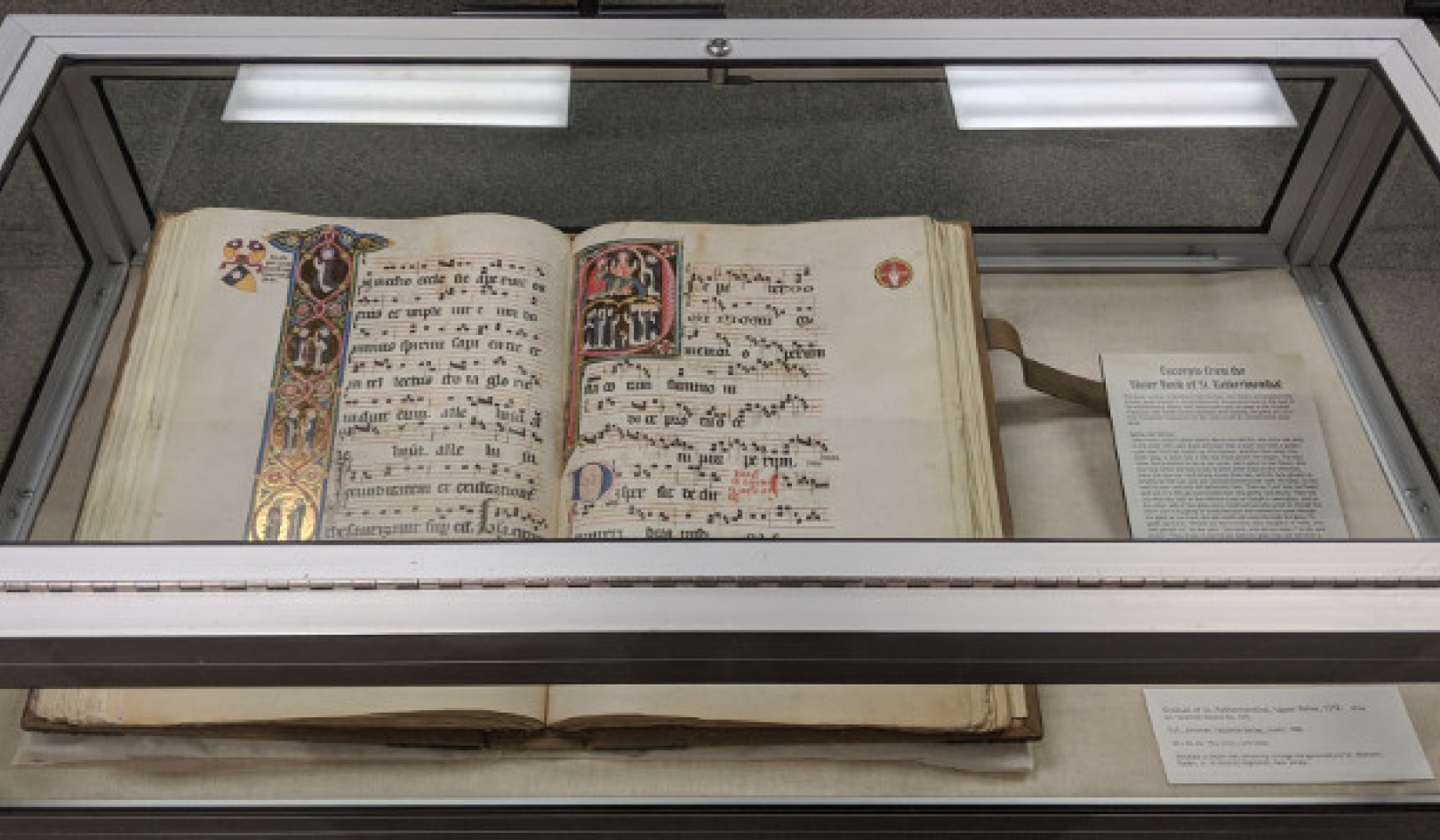

René Descartes’s illustration of dualism. Wikimedia Commons

René Descartes’s illustration of dualism. Wikimedia Commons

Most of these philosophies are heavily influenced by Rene Descartes’s concept of dualism, which separates the substances of body and mind. This idea of dualism is at the roots of the philosophical canon, from Immanuel Kant, to Friedrich Nietzsche, to David Hume. Founded in the primacy of knowledge and rationality, these philosophies culminate in the idea at the heart of the liberal philosophy of John Rawls and Ronald Dworkin: that for a debate to be moral, it must be capable of being rational. This is so we can use our minds to judge the actions of ourselves and others.

Some Western philosophers were more radical, such as Baruch Spinoza, a contemporary of Descartes. His major work, Ethics, opposed Cartesian dualism by unifying body and mind, God and substance. This also hugely influenced modern Western philosophy, particularly big, fashionable continental thinkers such as Martin Heidegger, John Paul Sartre and Jacques Derrida, who all have sought to place the body on equal philosophical terms with the mind. Despite being a leap forward, this philosophy still does not place all women’s bodies on equal philosophical footing with the minds of the men who wrote it.

A white male canon

All of the names listed above are white men. There is, of course, the huge body of (usually white) feminist work, but this is described as feminism, not philosophy. This means that we have a philosophy built by men, put on pedestal of genius, who defined and continue to define philosophy through their rational legacy.

This is despite the fact that Kant and Hume were racist and Aristotle (“the Father of Western philosophy”) was sexist. Heidegger was a member of the Nazi party, and as a professor began an affair with his then student, Hannah Arendt. The argument is that these philosophers were not as socially enlightened as us, given their historical specificity, so we should continue to value their ideas, if not their bodies.

This Cartesian insistence that philosophy can be separate from the body that writes it, can be dangerous. Sexist, racist, powerful (and sometimes abusive) men have been endowed with an authority to create the foundations of how we judge sex. We endow this philosophy with authority over all bodies: women of colour, queer women, trans women, women who like to have sex in all types of ways, women whose oppression and assault maintains the authority of these philosophical geniuses. These philosophers are dangerous since their authority can inform our sexual tastes, and what is “acceptable”. These rules encourage us to disregard the ethical complexities of women’s lives.

How could a canon of white men do justice to the complexities of women? Saeki/Shutterstock.com

How could a canon of white men do justice to the complexities of women? Saeki/Shutterstock.com

The pleasure of women

These philosophies were not helpful for me in my ethical dilemmas, since they were not written for me, my body and my sexuality. Thankfully, in the world outside of philosophy, core assumptions about women’s sexuality are being dismantled.

The academic Omise'eke Tinsley writes to empower the sexuality of black women generally, and against “misogynoir”, a specific sexism against black women. The writer Wednesday Martin, meanwhile, is systematically dismantling the myth that women are the monogamous ones, compared to men’s inherent sexual restlessness.

The movement to “correct” dominant ideas is not only about the sociology of women’s desire, but also the science. The OMGyes project is using research and women’s experiences to redefine a science of women’s pleasure. The Vulva Gallery is doing revolutionary work in sex education and representing women’s vulvas and their owner’s stories.

Sadly, we are not closer to finding a philosophical ethic that fits these growing understandings of women’s sexuality. There is the practical philosophy put forward by Dossie Easton and Janet Hardy in The Ethical Slut, but this is geared towards polyamorous people. And such an explicit code could be seen as unsexy, not to mention that some people might think of themselves as monogamous sluts, or something in between. Maybe some of us don’t want to be called sluts. And maybe there are those who prefer to be unethical. In the present philosophical landscape, who can blame them?

Future sexual ethics

So philosophically, we have not moved on. Psychoanalytic philosopher Alenka Zupan?i?’s What IS Sex aims to tell us what sex is in modern psychoanalytic and philosophical terms. But this does not help us discover a new kind of sexual ethics in light of what we have discovered and continue to discover about women’s practical sexual experiences. To do so, I argue that we need to move beyond the authority of even the male continental “radical” philosophical canon.

In my own ethical dilemmas, conventional ethics did not help me. In fact, they became part of the dilemma, since somehow I valued the perspective and empowered the words of my partner, because he was a philosopher. I also sat on that beach thinking that my desires were wrong, since they did not fit within a particular category, which meant I was not entitled to ethical treatment.

Also, as an academic, not only was I supposed to be objective and non-desiring, I was supposed to value ideas over bodily sensations. I was supposed to be rational and operate ethically while having my sexuality abused. Western ethics was not in favour of the strength of my body, but its destruction.

All this is to say that conventional philosophy and research is not going to develop a new ethics for women’s sexuality. Instead, as I argue in my story of finding my own sexual ethics, we need an ethic of vivid kindness, to ourselves and others. And it needs to be founded on a wholesale, orgasmic attack: on Western philosophy.![]()

About The Author

Victoria Brooks, Lecturer in Law, University of Westminster

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon