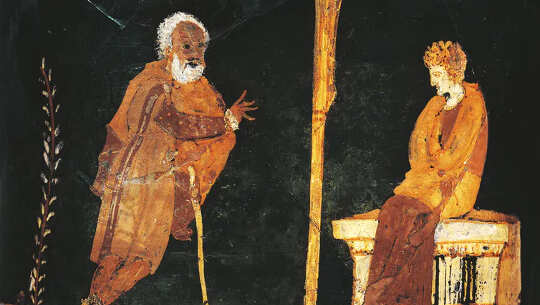

A vase from ancient Greek civilization depicts Apollo consulting the oracle of Delphi. G. Dagli Orti/DeAgostini Collection via Getty Images

Most of us take big and small risks in our lives every day. But COVID-19 has made us more aware of how we think about taking risks.

Since the start of the pandemic, people have been forced to weigh their options about how much risk is worth taking for ordinary activities – should they, for example, go to the grocery store or even turn up for a long-scheduled doctor’s visit?

As a scholar of ancient Greek history, I am interested in what the classics can teach us about risk-taking as a way to make sense of our current situation.

Greek mythology features godlike heroes, but Greek history was filled with men and women who were exposed to great risks without the comforts of modern life.

The iron generation

One of the earliest written works in Greek is “Works and Days,” a poem by a farmer named Hesiod in the eighth century B.C. In it, Hesiod addresses his lazy brother, Perses.

The most famous section of “Works and Days” describes a cycle of generations. First, Hesiod says, Zeus created a golden generation who “lived like the gods, having hearts free from sorrow, far from work and misery.”

Then came a silver generation, arrogant and proud.

Third was a bronze generation, violent and self-destructive.

Fourth was the age of heroes who went to their graves at Troy.

Finally, Hesiod says, Zeus made an iron generation marked by a balance of pain and joy.

While the earliest generations lived life free of worries, according to Hesiod, life in the current iron generation is shaped by risk, which leads to pain and sorrow.

Throughout the poem, Hesiod develops an idea of risk and its management that was common in ancient Greece: People can and should take steps to prepare for risk, but it is ultimately inescapable.

As Hesiod says, “summer won’t last forever, build granaries,” but for people of the current generation, “there is neither a stop to toil and sorrow by day, nor to death by night.”

In other words, people face the consequences of risk – including suffering – because that is the will of Zeus.

Omens and divination

If the outcome of risk was determined by the gods, then one critical part of preparing to face uncertainty was to try to find out the will of Zeus. For this, the Greeks relied on oracles and omens.

While the rich might pay to petition the oracle of Apollo at Delphi, most people turned to simpler techniques to seek guidance from the gods, such as throwing dice made of animal knuckle bones.

Marry, or stay single? Ancient Greeks, at times, let the dice decide. PHAS/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

A second technique involved inscribing a question on a lead tablet, to which the god would provide an answer such as “yes” or “no.” These tablets record a wide range of concerns from ordinary Greeks. In one, a man named Lysias asks the god whether he should invest in shipping. In another, a man named Epilytos asks whether he should continue in his current career and whether he ought to wed a woman who shows up, or wait. Nothing is known about either man except that they turned to the gods when confronted with uncertainty.

Omens were also used to inform almost every decision, whether public or private. Men called “chresmologoi,” oracle collectors who interpreted the signs from the gods, had enormous influence in Athens. When the Spartans invaded in 431 B.C., the historian Thucydides says, they were everywhere reciting oracular responses. When plague struck Athens, he notes that the Athenians called to mind just such a prophecy.

Chresmologoi played so much of a role in bolstering public confidence that the wealthy Athenian politician Alcibiades privately contracted them as spin doctors in order to persuade people to overlook the risks of an expedition to Sicily in 415 B.C.

Mitigating risks

For the Greeks, putting faith in the gods alone did not fully protect them from risk. As Hesiod explained, risk mitigation required attending to both the gods and human actions.

Generals, for example, made sacrifices to gods like Artemis or Ares in advance of battle, and the best commanders knew how to interpret every omen as a positive sign. At the same time, though, generals also paid attention to strategy and tactics in order to give their armies every advantage.

Neither was every omen heeded. Before the Athenian expedition to Sicily in 415 B.C., statues sacred to Hermes, the god of travel, were found with their faces scratched out.

The Athenians interpreted this as a bad omen, which may have been what the perpetrators intended. The expedition sailed anyway, but it ended in a crushing defeat. Few of the people who left ever returned to Athens.

The evidence was clear to the Athenians: The desecration of the statues had put everyone in the expedition at risk. The only solution was to punish the wrongdoers. Fifteen years later, the orator Andocides had to defend himself in court against accusations that he had been involved.

This history explains that individuals might escape divine punishment, but ignoring omens and failing to take precautions were often communal rather than individual problems. Andocides was acquitted, but his trial shows that when someone’s actions put everyone at risk, it was a community’s responsibility to hold them accountable.

Oracles and knuckle bones are not in vogue today, but the ancient Greeks show us the very real dangers of risky behavior, and why it is important that risk not be left to a simple toss of the dice.

About The Author

About The Author

Joshua P. Nudell, Visiting Assistant Professor of Classics, Westminster College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Related Books:

Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones

by James Clear

Atomic Habits provides practical advice for developing good habits and breaking bad ones, based on scientific research on behavior change.

Click for more info or to order

The Four Tendencies: The Indispensable Personality Profiles That Reveal How to Make Your Life Better (and Other People's Lives Better, Too)

by Gretchen Rubin

The Four Tendencies identifies four personality types and explains how understanding your own tendencies can help you improve your relationships, work habits, and overall happiness.

Click for more info or to order

Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don't Know

by Adam Grant

Think Again explores how people can change their minds and attitudes, and offers strategies for improving critical thinking and decision making.

Click for more info or to order

The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma

by Bessel van der Kolk

The Body Keeps the Score discusses the connection between trauma and physical health, and offers insights into how trauma can be treated and healed.

Click for more info or to order

The Psychology of Money: Timeless lessons on wealth, greed, and happiness

by Morgan Housel

The Psychology of Money examines the ways in which our attitudes and behaviors around money can shape our financial success and overall well-being.