Revenge in fiction can be shocking, but it often embeds a moral message. There is heroic revenge, a staple of the American movie world, in which the determined hero or anti-hero acts against an evil protagonist (the law being ineffective or absent). And there is righteous revenge, as in tales of women who exact bloody retribution on abusing men, a denouement that can bring cheers from an audience. Oppressors and bullies, goes the sentiment, often deserve what they get.

But beyond fiction, taming such revenge is, arguably, one of the most vexed questions of civilisation. Revenge may not always be the noblest of motives, but there are times when it can be defended, a message often occluded by sensationalist news reports: “Jilted wife joins forces with mistress to strip husband and smash a chair over his head in humiliating street revenge” reads one recent headline; “Mother of fourth grader threw a BRICK at teacher’s face then beat her after she confiscated her 10-year-old daughter’s cellphone” goes another.

As I explore in my new book, by sensationalising and deprecating the idea of revenge itself, we may forget that some forms of revenge can work well and serve a crucial purpose.

Revenge systems have been around for a very long time, with our primate cousins leading the way. Chimpanzees and macaques will freely inflict punishments on strangers and rule breakers and, with their excellent memories, cannily postpone retaliation until a suitable opportunity arises.

Revenge has also been vital to human tribes for protecting food sources, territory and social order: the threat of swift retaliation for cheating, stealing, bullying or killing can be an effective deterrent. Stripped of its pejorative association, revenge can simply be seen as quintessential justice for the avenger. It’s about responding to harm with harm: “getting even”, “tit for tat”, an “eye for an eye” – you’re someone not to be trifled with.

Revenge restores the balance and reclaims status. It can be instant, fuelled by rage, or deferred, a dish served cold. For abuse sufferers, revenge can sometimes feel like the only way out – for example, Virginian housewife Lorena Bobbitt in the 1990s. After years of infidelity and sexual abuse from her husband, she grabbed a kitchen knife and sliced off her drunken husband’s penis (the member was subsequently reattached). The jury sympathised with her poetic reckoning, and she went on to publicly champion the rights of abused women. But not all penis-severers have been received so charitably. This is evidence, some say, of misogyny in justice systems.

Revenge is especially tough to dislodge when ingrained in the identity of a group, like street gangs committed to the violent protection of their territory, spoils or “respect”, and families entrenched in patriarchal honour, prepared to turn savagely on their own.

But, in daily interactions, revenge also has a softer face, like the airline check-in clerk who, after a string of abuse from a customer, politely wishes him a good flight and then quietly redirects his bags elsewhere. Or the offensive diner whose credit card is “inexplicably rejected I’m afraid, sir” – or whose soup is spiced with spittle. Covert revenge – service sabotage – salvages a little self-respect in a world where customers are prepared to exploit their “kingly” status.

In complex societies, free-wheeling revenge undermines a ruler’s control; it’s wild justice. A basic given for civic order is that the state appropriates revenge. Justice is codified. Punishment is the state’s prerogative, revenge by another name. This will suppress vigilantism – up to a point. People will be inclined to seek extrajudicial means when they believe the justice system is skewed against them because of their ethnicity, status, skin colour or gender.

In India, for example, rape cases can last for years, or never come to court, the police more disposed to blame the victim rather than arrest the perpetrator. In 2004, this came to a head with particular symbolic significance in a village courtroom. Some 200 incensed women attacked and killed a serial rapist who was there on trial. The women’s trust in the legal system was zero, and their anger boiled over when the man publicly threatened them in court. He had terrorised the low caste community with impunity for years, buying off the local police.

A few years later, the women of Kerala followed suit. A furious group of them delivered vigilante justice to two local rapists, tying them naked to railings and beating them, before handing them over to the police. And in South America, hundreds of cases of citizen’s revenge have been documented. Recently, residents of Teleta del Volcán in Mexico beat a woman and four men, tied them to poles and threatened to burn them alive. These victims were members of a syndicate that included former and current police officers that, allegedly, specialised in extortion and kidnapping.

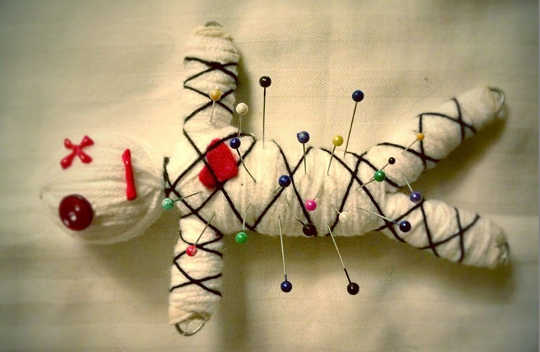

![]() Here we witness desperate acts by desperate people who know they are not being protected by the state. They have reached a tipping point – and who can blame them?

Here we witness desperate acts by desperate people who know they are not being protected by the state. They have reached a tipping point – and who can blame them?

About The Author

Stephen Fineman, Professor Emeritus in Organization Studies, University of Bath

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Related Books:

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon