"It was indeed an 'unusual' judicial sentence of two white teenagers for racist graffiti sprayed on a historic black school in northern Virginia: 'read from a list of 35 books, one a month for a year, and write a report on all twelve to be read by your parole officers.'" -- New York Times, Feb. 9, 2017, p. A20

I thought: “At last, a punishment that really fits a crime!”

The only downside was that, when carried out, the books, in the minds of these two readers, were likely to be shadowed forever by associations with punishment. For me that would be tragic, given the fact that for millions of readers, myself included, this list of 35 books long ago helped alert us to the deep wrongs of racism in modern society: among them, Cry the Beloved Country by Alan Paton, To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou, Night by Elie Wiesel and Black Boy by Richard Wright.

The remarkable feature of this judicial sentence was how it clashed conceptually with the customary default question that suffuses our judicial system as a whole: How long a prison sentence does the crime deserve? That question penetrated many a conversation last year in the case of a university student in California sentenced to six months in prison for rape. A large protest greeted this mild sentence, but it provoked from the father of the accused the counter protest that even six months was a severe punishment for what was probably “20 minutes of action” for his rapist son. He did not suggest that anything but pleasant was the experience of the young woman.

A strange mathematics is at work in our criminal justice system: for every crime, a matching time in prison. Philosophers speak often of the difficulty of comparing “apples and oranges.” Those are different fruits, not to be put into the same categorical basket. A more technical description of that maneuver might be “the fallacy of misplaced concreteness.” Translating the crime of racist graffiti into reading books that might reform the minds of two teenagers makes a certain concrete rational match with the crime. Putting them in prison for five years is no match at all.

Somewhere in the march from qualitative to quantitative assessments of human behavior, we tolerate leaps that deny rationality. In the recent era of mandated sentences for drug possession, judges themselves have sometimes protested the effects of such law. In 2002, in Utah, one Weldon Angelos, age 22, was issued a sentence of 55 years in prison for trying to sell a half pound of marijuana. Judge Paul Cassell, a Bush appointee, called his own mandated sentence “unjust, cruel and even irrational.” Twelve years into that sentence, another federal judge reduced the sentence and released Angelos.

Is there any consistently rational formula for matching years in prison to the seriousness of a crime? How much prison time per crime? Indeed, why prison as our customary response to virtually all of the 5,000 crimes counted by the Heritage Foundation on the 27,000 pages of the US Code? Without question the typical inquiry in any court about penalties for anyone found guilty of these and crimes-in-general centers on the question, “How much time in prison?”

The questions are old and embedded deep in our legal culture. Medieval castles routinely included dungeons in their building plans. In his Notes on the State of Virginia, written in the early 1780s alongside his tortured reflections on slavery, Thomas Jefferson proposed a “revised code to proportion crimes and punishments” drawn from traditions of English common law and ancient Roman precedent. He proposes to pre-Constitution readers a scale of crimes and punishments raging from the death penalty for “high treason” but to impunity for “suicide, apostasy and heresy” (which in a rationalistic age are “to be pitied, not punished.”) Prominent in his list of 22 matches is his assumption that murder and treason deserve the death penalty, but rape, sodomy and arson do not. Lingering from medieval law in his list is his apparent toleration of petty treason’s punishment by “dissection,” which recalls extra-special executions by hanging, disembowelment and dismemberment that remained in English law into the 19th century.

Still for the founding generation was a Bill of Rights that was to forbid “cruel and unusual punishment.” Prominent in Jefferson’s list, however, was his belief that justice for the taking of life or property should both require confiscation of the perpetrator’s property on behalf of victims and “the commonwealth.”

A certain leap toward the irrational was inherent here. How to justify a return of stolen property to the state rather than the original possessor? Some legal philosophies would answer, perhaps, that all crime is an assault on the larger community represented by government. One might conclude that requiring the guilty to pay court costs makes sense. Not so sensible is the abstraction that a state that makes the laws is the victim of the crime.

As the restorative justice movement would insist, when feasible the just remedy of damages to victims should have a larger place in our ideas about “criminal justice.” Victims of thievery need not only the symbolic satisfaction that the perpetrator will suffer some punishment but rather that the perpetrator will pay back the value of the things stolen.

We should study the history behind Jefferson’s crime-and-punishment catalogues carefully to learn why American law eliminated some of his formulas. Just so, much history of our current crisis is implicit in the “sentencing table” passed by the US Congress between 1987 and 2010 for non-mandatory guidance of federal criminal courts. This document is a marvel of lawyerly specification of alleged fits between crimes and punishments. Divided between four “zones” of increasing severity of crimes adjusted by “criminal history points,” the recommended sentences range from six months to life imprisonment to capital punishment.

I understand that this chart, while not mandatory, is now followed by many federal judges as a guide since it has the endorsement of Congress and thus lifts some of the discretionary burden of decision from working judges.

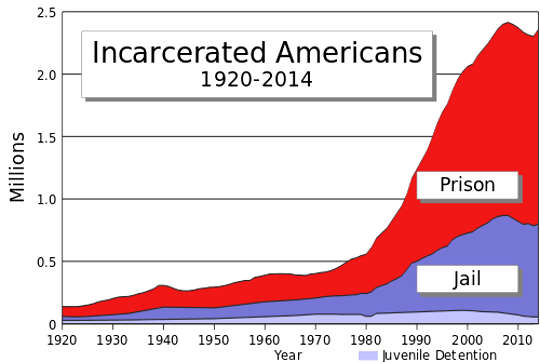

But again, there is something narrow, deceptive and potentially cruel in all this quasi mathematical calculation of legal justice, beginning with our “default” assumption of prison as society’s response to crime. So pervasive and typical is this resort to imprisonment that, in all due irony, we might conclude that in an era when our prisons are overcrowded with inmates convicted of drug charges, our criminal justice system itself is addicted to imprisonment.

This addiction deserves our scrutiny, and that in at least three dimensions: (1) economic, (2) political and (3) moral.

(1) American society spends at least $80 billion on our incarceration of 2.3 million citizens. It has yet to be proven that the $60,000 we spend annually in New York State to keep a lawbreaker behind bars is money well spent for reducing crime. In-prison education and a post-prison job are better restraints on recidivism. Fifty percent of jobless exprisoners, a recent US Court office research found, are likely to return to prison in contrast to 7 percent of the post-prison employed.

(2) In general, politics puts people in prison and keeps them there. Adam Hochschild recently noted that the American system of electing judges and prosecutors makes them sensitive to oncoming election seasons, so that, in the state of Washington, for one, judges tended to raise their sentences by about 10 percent on the eve of their standing for election. Ordinary in our politics is the power of “tough on crime” arguments for severe prison sentences. This, in the face of the doubt that social scientists have long cast on the notion that the longer one’s time in prison, the less likely one is to offend again. In fact, prisons school many inmates in skills that serve future criminality. For every exprisoner who finds prison to be a real “penitentiary,” there is another who agrees with an ex-prisoner in Milwaukee who told sociologist Matthew Desmond, “Prison ain’t no joke. You gotta fight every day in prison, for your life.”

(3) Discussion of the moral issues of crime and punishment are often very superficial in our religious institutions. I can hardly count the times in church discussions when someone quotes Exodus 21:24 — “life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth,” as though this formula for tit-for-tat revenge is the heart of the Hebrew Bible’s message about social response to human misbehavior. Few quoters of 21:24 seem aware of the following verse that supports the idea of restorative justice with the instruction that, if a slave owner so much as knocks out a tooth of a slave, that slave should be freed. Exodus 21 uses terms like “restitution” as responses to lawbreaking in common with norms of restorative justice.

Moreover, as regards punishment for human sin in general, the Bible, from Genesis to Revelation, is full of teachings that ask believers to imitate a “justice” of God that is suffused with mercy and forgiveness, a belief as basic to the prophets of Israel as to the teachings of Jesus.

Students of criminal justice would do well to repair to Robert Frost’s poem “The Star-splitter,” that tells the story of an astronomy-loving farmer who goes to prison after being convicted of burning down his barn to secure money for the purchase of a telescope. After his year in jail, his neighbors have to decide if they can treat him as a neighbor now. Well, says the poet, what if we counted no one worthy of citizenship after some breaking of law? Indeed,

If one by one we counted people out

For the least sin, it wouldn’t take us long

To get so we had no one left to live with.

For to be social is to be forgiving.

The poem, like many a passage in the Hebrew and Christian Bibles, does not suggest that some punishment for crime is contrary to forgiveness, but rather holds out hope for the perpetrator recovering his or her citizenship.

To be sure, a passion for matching varieties of crime and punishments is not wholly mistaken, for crimes do occur in different degrees of damage to victims. But human virtues and vices can scarcely be translated into mathematical values, not to speak of years in prison. In her widely read book, The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander targets the absurdity of the “three strikes” law in California (now abolished) which, in one case, resulted in punishing a theft of three golf clubs with 25 years in prison without parole. Another theft of five videotapes got a sentence of 50 years without parole. As Supreme Court Justice David Souter exclaimed, if this latter sentence “is not grossly disproportionate, the principle of fitting punishment to crime has no meaning.”

We have to wonder if the principle itself has been losing its meaning over centuries of its dominance in our criminal justice systems.

This post first appeared on BillMoyers.com.

About The Author

Donald W. Shriver Jr. is an ethicist and an ordained Presbyterian minister who has belonged to the U.S. Council on Foreign Relations since 1988 and was president of Union Seminary from 1975 to 1991. His writings have concentrated on case studies of countries in the area of conflict transformation, including the U.S. and its struggles for justice in race relations. His publications include An Ethic For Enemies: Forgiveness in Politics (1998) and On Second Thought: Essays Out of My Life (2009). In 2009 he was awarded the 18th Grawemeyer Award in Religion for the ideas he set forth in his book, Honest Patriots: Loving a Country Enough to Remember Its Misdeeds (2008).

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon