A worldwide consortium of 70 scientists has completed the most detailed climatic history of the planet so far during the last 2,000 years.

They used evidence from ice cores, tree rings, preserved pollens, coral growth rings, stalagmites, lake sediments, sea bed cores, old documents and modern instruments to chart change not just of the globe itself, but of climate change in seven continental regions.

500 Different Sets of Temperature Records Used

Altogether, they looked at more than 500 different sets of temperature records from all the continents except Africa, where the evidence is still incomplete.

The ambition united botanists from Pakistan and China, archaeologists from Norway, glaciologists from Germany and Tasmania, foresters from Japan and so on: experts who knew their field, and their territory.

No Evidence For A Worldwide Medieval Warm Period or A Little Ice Age

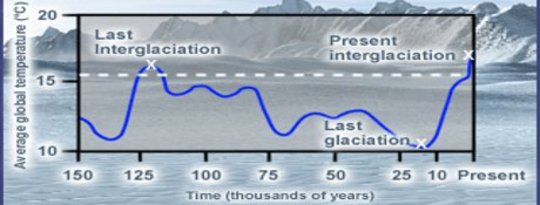

They could find no evidence for a worldwide Medieval Warm Period or a Little Ice Age: that is, these documented events were real enough in Europe but scientists could not detect such a distinctive warming or cooling period everywhere on the planet at the same time.

In the northern hemisphere, there was a warm period from AD 830 to 1100; in Australia and South America there was a warming spell from AD 1160 to 1370.

But they did confirm that a long period of global cooling ended in the late 19th century. They confirm that conditions everywhere were generally cold between 1580 and 1880, and they confirm that the 30-year-period between 1971 and 2001 was the warmest on land in at least 1,400 years.

“Nowadays we know how important it is to have a better understanding of regional differences”

Global Climate Averages Are Just Averages

Global climate averages are just that: averages. They do not and cannot illuminate change in very differing climatic zones or land masses: notoriously, even in a warming world, Britain and Western Europe may experience an unseasonably cold wet summer while the 48 contiguous states of the mainland US swelter through record-breaking heat waves and sustained drought.

So to devise a real basis for testing new models of climate change for the future, a 70-strong consortium called PAGES 2K – the acronym stands for Past Global Changes, and the 2K for the ambition to build up a clear picture of difference and similarity from the Roman Empire to the present-day – took a fresh look at history.

They report on what they can and cannot confirm in the pages of Nature Geoscience. For the first 1,700 years of the research period there were no thermometers, no precise scales of measurement and no systematic data collection. So the researchers turned to proxies.

Tree ring growths can – if you look at enough trees – answer questions about warm and cold summers; ice cores and marine sediments can reveal a lot about patterns of annual change; stalagmites and coral growths are carbonate testaments to gradual change.

Even so, the evidence was limited: the Arctic, Europe and Antarctica yielded a complete record of the whole 2000 years. Climate history in Asia, South America and Australasia could be counted back for only 1,000 to 1,200 years at the most.

Tree rings in North America told researchers the detailed history of the continent from AD 1,200; fossilized and preserved pollens took the story of the US, Mexico and Canada back to AD 360.

The Research Delivers No Great Surprises

The research delivers no great surprises – that is, it broadly confirms the story told repeatedly by climate scientists for the last 30 years – but it does provide a snapshot of science in action, and a benchmark for future studies.

So far the PAGES team can provide a cautious account of climate change covering just 36% of the Earth’s surface for at least 1,000 years, and in some cases 2,000 years. What makes the study unique, and important, is that for the first time researchers can compare patterns of change on almost all of the continents.

“Even just a few years ago we would have aimed for a single worldwide temperature series”, said Ulf Büntgen of the Swiss Federal Research Institute, one of the co-authors. “Nowadays we know how important it is to have a better understanding of regional differences.” – Climate News Network

radfor_bio

climate_books