Economic inequality is high and rising. At the same time, many governments are struggling to balance budgets while maintaining spending for popular programs.

As White House aspirants, other politicians and voters debate whether it’s time to once again soak the rich to spread their wealth around, it’s helpful to consider what prompted past governments – ours and others – to raise their taxes.

We investigated tax debates and policies in 20 countries from 1800 to the present for our book, “Taxing the Rich: A History of Fiscal Fairness in the United States and Europe." Our research shows that it is changes in beliefs about fairness – and not economic inequality or the need for revenue alone – that have driven the major variations in taxes on high incomes and wealth over the last two centuries.

In general, societies tax the rich when people believe that the state has privileged the wealthy, and so fairness demands that the rich be taxed more heavily than the rest. To understand whether today’s voters are ready to tax the rich requires identifying the political and economic conditions that drive these beliefs.

Debating taxation

Debates about taxation typically revolve around self-interest (no one likes paying taxes), economic efficiency (tax policies should be good for economic growth) and fairness (the state should treat citizens as equals).

While it’s easy to see how self-interest and considerations about economic growth influence changes in tax policy, it’s harder to discern how fairness fits into the equation. In fact, our research suggests that fairness has played a key role in either generating a consensus around raising taxes on the rich or lowering them.

Politicians and others tend to use three arguments about fairness to support or oppose taxing the well-to-do:

-

“Equal treatment” arguments claim that everyone should be taxed at the same rate, just like everyone has one vote.

-

“Ability to pay” arguments contend that states should tax the rich at higher rates because they can better afford to pay more compared with everyone else.

-

“Compensatory” arguments suggest that it is fair to tax the rich at higher rates when this compensates for unequal treatment by the state in some other policy area.

Over the last 200 years, of all the varying arguments used to support raising taxes on the rich, our research suggests that compensatory claims, especially during mass mobilization wars, have been the most powerful.

When these arguments are credible, a consensus for taxing the rich shapes policymaking.

Time to tax the wealthy

Compensatory arguments were important in the early development of income tax systems in the 19th century when it was argued that income taxes on the rich were necessary to counterbalance heavy indirect taxes (e.g., sales taxes) that fell disproportionately on the poor and middle class.

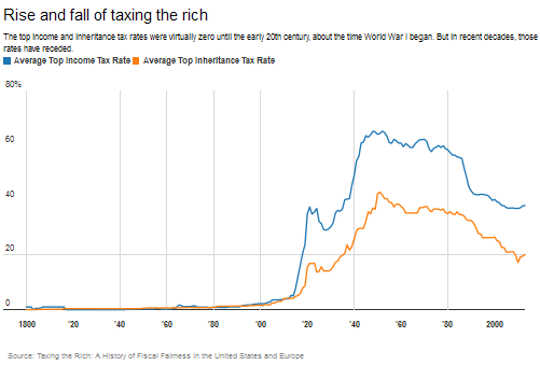

The chart below shows when countries raised or lowered taxes on the rich, based on average top income and inheritance rates since 1800.

As you can see, the real watershed moment for taxing the rich for many countries came in 1914. The era of the two world wars and their aftermath was one in which governments taxed the rich at rates that would have previously seemed unimaginable.

In fact, as our research shows, the most significant compensatory-based justifications for raising taxes on the rich have been to preserve equal sacrifice in wars of mass mobilization, such as World Wars I and II. This was true for both governments of the left and the right.

These conflicts forced states to raise large armies through conscription, and citizens and politicians alike argued that there should be an equivalent conscription of wealth.

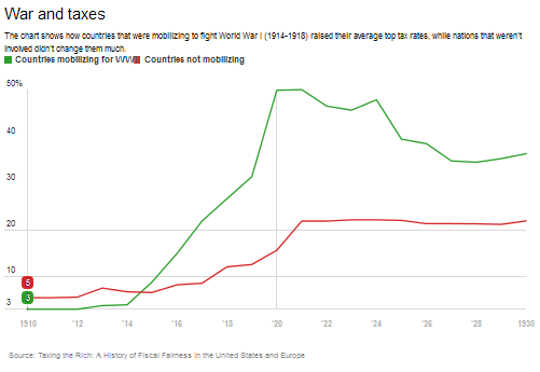

The next chart shows this effect clearly by comparing average rates in countries that did and did not mobilize for World War I.

Conscripting wealth

If mobilization for mass warfare is when major changes in taxes on the rich occurred, how do we know that the effect of these wars was due to changes in fairness considerations?

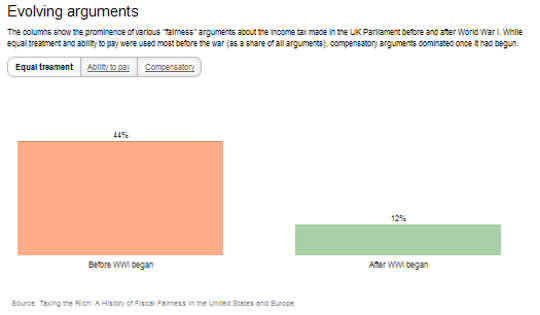

As we examine in detail in our book, when countries shifted from peace to war, or the reverse, there was also a shift in the type of tax fairness arguments made. During times of peace, debates about whether it is fair to tax the rich center on equal treatment versus ability to pay arguments. It was primarily during times of war that supporters of taxing the rich were able to make compensatory arguments.

An example of this type of argument goes like this: if the poor and middle class are doing the fighting, then the rich should be asked to pay more for the war effort. Or, if some wealthy individuals benefit from war profits, then this creates another compensatory argument for taxing the rich.

The following graph shows how the composition of fairness arguments changed in parliamentary debates in the UK before and after World War I.

We also found that these compensatory arguments had the biggest impact in democracies, such as the United Kingdom and United States, in which the idea that citizens should be treated as equals is the strongest.

Why taxes on the rich declined

Although tax rates on the rich stayed high for a few decades after the major wars of the 20th century, they have declined substantially over the last 40 years. Does this decline give us further clues about the long-run determinants of what arguments work to impose higher taxes on the rich?

The most important factor has been that in an era in which military technology favors more limited forms of warfare – cruise missiles and drones rather than boots on the ground – the wartime compensatory arguments of old can no longer be used in national tax debates. Without conscription, these arguments are not credible.

In this new technological era, advocates of reducing taxes on the rich have argued that fairness demands equal treatment, while proponents of taxing the rich have been forced to fall back on traditional ability to pay arguments – that the wealthy should pay more because they can afford it. With compensatory arguments gone, in most countries the consensus for high taxes on the rich eroded over time.

We also considered the role that changing concerns about economic incentives and the role of globalization may have played in the decline in rates but found little evidence when it comes to personal income and wealth taxes.

What this means today

What can we conclude for today’s tax debates from all of this?

Our research suggests we should not expect high and rising inequality alone to lead to a return to the high top tax rates of the post-war era, when U.S. taxes peaked at over 90 percent. This is the lesson to draw from history, and it also fits with what many American voters prefer today.

When we conducted a survey for our book on a representative sample of Americans, we found only minority support for implementing a tax schedule with radically higher taxes on the rich than the one in place today.

At the same time, citizens still care a great deal about fairness. As in other eras not dominated by war mobilization, their fairness beliefs are primarily formed by equal treatment and ability to pay views, without a consensus for high rates.

Still, even though there seems to be limited room for large changes in top statutory or marginal rates, contemporary views on fairness suggest there would be support for important reforms so that the rich pay higher effective rates.

In the U.S., sometimes the rich actually pay a lower effective tax rate than everyone else because of loopholes and other privileges in the tax code. This is the main argument in favor of the Buffett rule, named after billionaire investor Warren Buffett.

The rich paying a lower share of their income than everyone else clearly violates our sense of fairness, whether you are a proponent of equal treatment for all taxpayers or argue the rich should pay more because they are best able to. Reforms to address these privileges should be something both groups can agree on.

About The Authors

Kenneth Scheve, Professor of Political Science, Stanford University. His current research projects include comparative studies examining the role of social preferences in opinion formation about tax policy, trade policy, and international environmental cooperation as well as work on the political origins of changes in wealth inequality in the 19th and 20th century.

David Stasavage, Julius Silver Professor, Department of Politics, New York University. His work has spanned a number of different fields and currently focuses on two areas: development of state institutions over the long run and the politics of inequality.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Recommended books:

Capital in the Twenty-First Century

by Thomas Piketty. (Translated by Arthur Goldhammer)

In Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty analyzes a unique collection of data from twenty countries, ranging as far back as the eighteenth century, to uncover key economic and social patterns. But economic trends are not acts of God. Political action has curbed dangerous inequalities in the past, says Thomas Piketty, and may do so again. A work of extraordinary ambition, originality, and rigor, Capital in the Twenty-First Century reorients our understanding of economic history and confronts us with sobering lessons for today. His findings will transform debate and set the agenda for the next generation of thought about wealth and inequality.

In Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty analyzes a unique collection of data from twenty countries, ranging as far back as the eighteenth century, to uncover key economic and social patterns. But economic trends are not acts of God. Political action has curbed dangerous inequalities in the past, says Thomas Piketty, and may do so again. A work of extraordinary ambition, originality, and rigor, Capital in the Twenty-First Century reorients our understanding of economic history and confronts us with sobering lessons for today. His findings will transform debate and set the agenda for the next generation of thought about wealth and inequality.

Click here for more info and/or to order this book on Amazon.

Nature's Fortune: How Business and Society Thrive by Investing in Nature

by Mark R. Tercek and Jonathan S. Adams.

What is nature worth? The answer to this question—which traditionally has been framed in environmental terms—is revolutionizing the way we do business. In Nature’s Fortune, Mark Tercek, CEO of The Nature Conservancy and former investment banker, and science writer Jonathan Adams argue that nature is not only the foundation of human well-being, but also the smartest commercial investment any business or government can make. The forests, floodplains, and oyster reefs often seen simply as raw materials or as obstacles to be cleared in the name of progress are, in fact as important to our future prosperity as technology or law or business innovation. Nature’s Fortune offers an essential guide to the world’s economic—and environmental—well-being.

What is nature worth? The answer to this question—which traditionally has been framed in environmental terms—is revolutionizing the way we do business. In Nature’s Fortune, Mark Tercek, CEO of The Nature Conservancy and former investment banker, and science writer Jonathan Adams argue that nature is not only the foundation of human well-being, but also the smartest commercial investment any business or government can make. The forests, floodplains, and oyster reefs often seen simply as raw materials or as obstacles to be cleared in the name of progress are, in fact as important to our future prosperity as technology or law or business innovation. Nature’s Fortune offers an essential guide to the world’s economic—and environmental—well-being.

Click here for more info and/or to order this book on Amazon.

Beyond Outrage: What has gone wrong with our economy and our democracy, and how to fix it -- by Robert B. Reich

In this timely book, Robert B. Reich argues that nothing good happens in Washington unless citizens are energized and organized to make sure Washington acts in the public good. The first step is to see the big picture. Beyond Outrage connects the dots, showing why the increasing share of income and wealth going to the top has hobbled jobs and growth for everyone else, undermining our democracy; caused Americans to become increasingly cynical about public life; and turned many Americans against one another. He also explains why the proposals of the “regressive right” are dead wrong and provides a clear roadmap of what must be done instead. Here’s a plan for action for everyone who cares about the future of America.

In this timely book, Robert B. Reich argues that nothing good happens in Washington unless citizens are energized and organized to make sure Washington acts in the public good. The first step is to see the big picture. Beyond Outrage connects the dots, showing why the increasing share of income and wealth going to the top has hobbled jobs and growth for everyone else, undermining our democracy; caused Americans to become increasingly cynical about public life; and turned many Americans against one another. He also explains why the proposals of the “regressive right” are dead wrong and provides a clear roadmap of what must be done instead. Here’s a plan for action for everyone who cares about the future of America.

Click here for more info or to order this book on Amazon.

This Changes Everything: Occupy Wall Street and the 99% Movement

by Sarah van Gelder and staff of YES! Magazine.

This Changes Everything shows how the Occupy movement is shifting the way people view themselves and the world, the kind of society they believe is possible, and their own involvement in creating a society that works for the 99% rather than just the 1%. Attempts to pigeonhole this decentralized, fast-evolving movement have led to confusion and misperception. In this volume, the editors of YES! Magazine bring together voices from inside and outside the protests to convey the issues, possibilities, and personalities associated with the Occupy Wall Street movement. This book features contributions from Naomi Klein, David Korten, Rebecca Solnit, Ralph Nader, and others, as well as Occupy activists who were there from the beginning.

This Changes Everything shows how the Occupy movement is shifting the way people view themselves and the world, the kind of society they believe is possible, and their own involvement in creating a society that works for the 99% rather than just the 1%. Attempts to pigeonhole this decentralized, fast-evolving movement have led to confusion and misperception. In this volume, the editors of YES! Magazine bring together voices from inside and outside the protests to convey the issues, possibilities, and personalities associated with the Occupy Wall Street movement. This book features contributions from Naomi Klein, David Korten, Rebecca Solnit, Ralph Nader, and others, as well as Occupy activists who were there from the beginning.

Click here for more info and/or to order this book on Amazon.