Tania Morales de la Cruz, a professor of education at Cuba’s University of Matanzas, recently visited South Africa for the first time. She chats to Dr Clive Kronenberg of the Cape Peninsula University of Technology about the island nation’s lessons for other countries – especially when it comes to rural and multi-grade education (in which children of different ages and grade levels share one classroom and teacher), as well as the role of culture in education.

Rural education remains a major challenge throughout the world. Cuba seems to have flourished where many others have faltered?

Cuba has paid special attention to rural education since the early 1960s. Communities and teachers work together to fulfil the objective of bringing good, quality education to all. The aim is to provide all children with the same possibilities: to help them attain a high understanding of their culture so they can contribute to social development and integration.

Teachers, student teachers, retired teachers and fully-trained assistants are all indispensable to the smooth functioning and success of our many rurally-based schools.

There are thousands of small, often underdeveloped multi-grade schools around the world, mostly in rural areas and fairly invisible to the public eye. My own visits to Cuba showed that it also faced this predicament. How did Cuba address this in meaningful, productive ways?

The multi-grade classroom –- where one teacher instructs two, three or more grades at the same time – has become a valuable stepping stone in our rural communities. Here the preparation of teachers has been planned with significant dedication. In Cuba’s rural districts, multi-grade classes have successfully delivered quality education to a wide age-range. The curricula have been customised to address this range.

Instructional materials are regularly updated with relevant content. They’re then rolled out cost effectively – using, for instance, TV lessons both at school and at home.

The use of approaches aimed at the classroom-group, as a whole, and not the individual grade, has been very fruitful.

Research shows high levels of apathy and boredom among rural students all over the world. This makes sense, since rural areas tend to lack cultural and social amenities. Is this why Cuba placed a high value on culture to deal with this?

Being rural doesn’t mean that schools cannot carry out projects with parents and children such as regional song, dance and poetry festivals. Drama productions, film shows and debates about topics crucial to the curriculum have raised both Cuban school children’s cultural levels and their educational experience. This is also true for those living in far flung, isolated regions.

Book fairs, together with school and community libraries, have promoted literacy and, ultimately, the broadening of consciousness. In our rural districts, as elsewhere, cultural events aimed at “celebrating excellence” are regularly organised. The emphasis is not so much on “competition” but on “emulation” – matching or even going beyond the “striking” and “remarkable”.

How is this “cultural developmental process” manifested at basic school level?

Cultural development as part of the daily curriculum is extensive, none the least in our rural schools.

Communities and parents remain deeply involved. Cubans understand that one cannot separate culture from education or education from culture. Here parents play a key role. They are empowered, encouraged and resourced to do as much early childhood development as possible with their children. But we also have hosts of specialised schools for gifted children – from anywhere - to receive expert tuition in the expressive arts.

What basic lessons do you think could be applied to improve education in South Africa’s own rural hinterlands?

In my visit to the country’s rural areas I could appreciate that what you really need is more commitment to secluded teachers and the special conditions they face. More pronounced methodological guidance can certainly be beneficial as well. Perhaps more organised supervision, coupled with the sharing of experiences and the design of lessons, can all contribute to raising standards and results.

How can South Africa begin to overcome its seriously impaired education system? Previously you have highlighted the importance of “values” in enhancing the educational process…

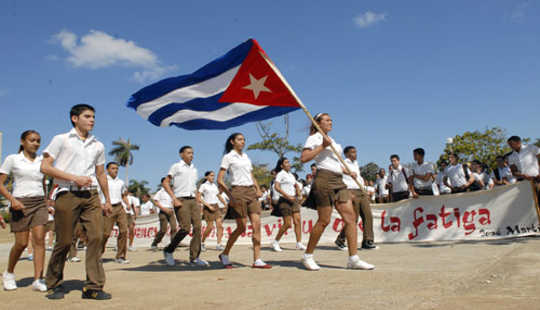

It was through the unity of the nation that Cuba could work together as one to attain this high standard in education – but also in culture, in the arts, in health, in ecological protection. The promotion of a shared, universal values system was considered crucial to forming a new, unified nation.

Such processes, envisioned by the national hero José Martí and taken up by the leadership, played a pivotal part in the children’s educational advancement. Without a good, universal values system, the educational project would not have reached the heights it currently commands.

You seem to suggest that a “moral imperative” may be lacking in South Africa?

I cannot be prescriptive. But it all starts with the economy, which should be deeply linked to the social development and upliftment of the population as a whole. More and more groups across the world are opposing social systems that are reactionary in nature, by standing up for real, progressive change. This could be advanced by focusing even more on the impact of culture on youth.

Are you saying that productive social and cultural change is key to overcoming our struggling education system?

South Africa should think about committing to the holistic development of all children. This should include the formation of a cohesive social identity without the fastidious focus on individualism, particularism and materialism.

Here Cuba’s educational policy is closely linked to its cultural policy, where the cultural triumphs of other societies are fully incorporated into its national programmes. At the same time, we place a high premium on our national traditions. But our major quest has been not so much to elevate and revere individual cultures, but also to look for and build on common premises.

And the end result?

We have achieved a fair measure of success in bringing different cultures – and by association, “different peoples” and “different traditions” – together under a fully co-operative nationhood. The triumphs of our education system depended on the formation of a socially interconnected community of citizens working together for the common good of all.

Author’s note: This scholarly visit was funded with a grant from the South African National Research Foundation. Thanks to others who make the visit a success including: Laura Efron (Argentina), Nyarai Tunjera (Zimbabwe), Merle Hodges (Director: CPUT International Office), Dr Karen Dos Reis (HOD: CPUT Education Faculty), Professor Meschach Ogunniyi (UWC), Professor Johann Wasserman (UP), and Dr Diphane Hlalele (UFS).

About The Author

Clive Kronenberg, NRF Accredited & Senior Researcher; Lead Coordinator of the South-South Educational Collaboration & Knowlede Interchange Initiative, Cape Peninsula University of Technology

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Related Books:

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon