The fragmentation of global production has dramatically increased the length and complexity of supply chains. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimates that more than half of the world’s manufactured imports are intermediate goods. These are used as inputs in the production of other goods, sourced from different parts of the globe.

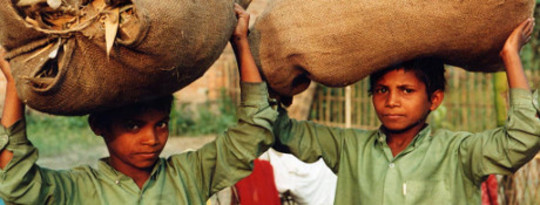

A serious problem with such long and complex supply chains is that this can lead to a lack of oversight and worker exploitation such as the use of child and forced labour, for estimated profits of US$150 billion a year. At our end of the supply chain, demand for low-cost goods can push suppliers towards abusive practices. These malpractices can affect individuals, producers and consumers anywhere in global supply chains.

This makes Australia part of the problem and the potential solution. Increasingly, companies and investors work with trade unions and NGOs to deal with labour and human rights abuses in supply chains. Yet, in a report launched this week, Catalyst Australia shows that misunderstandings about child labour persist and room for improvement remains.

The report coincides with the Australian government’s announcement of a Supply Chains Working Group to tackle these problems.

Child Labour Remains Widespread

Global initiatives and national laws have not made child labour history. Although it is estimated to have declined by 33% since 2000, 168 million children continue to be exploited worldwide. While global conventions are in place, their existence does not guarantee local take-up, nor does the existence of national child labour laws mean they are actively enforced.

A false perception persists that child labour affects only developing countries. However, in 2013, more than half of Australia’s imported goods came from the Asia-Pacific region, which has the largest absolute number of child labourers: 78 million.

It is also incorrect that only isolated industries use child labour. While 59% of child labour happens in agricultural settings, the manufacturing and services sector are significant contributors.

Catalyst Australia finds that self-regulatory standards and voluntary initiatives alone do not drive change. They are often merely public relations tools. Neither do charitable donations absolve companies of their responsibilities.

As John Ruggie, author of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, states:

There is no equivalent to buying carbon offsets in human rights: philanthropic good deeds do not compensate for infringing on human rights.

Forced Labour Generates Huge Profits

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) estimates that 20.9 million people globally are subjected to forced labour, 90% of whom are exploited in the private sector. Of these individuals, 68% are forced to work in agriculture, construction, domestic work, mining and manufacturing.

The Asia-Pacific region accounts for 11.7 million individuals in forced labour – 56% of the global total.

The ILO estimates that forced labour in the private economy generates US$150 billion in profits annually. Two-thirds is estimated to come from sexual exploitation. The rest comes from forced labour in construction, manufacturing, mining and utilities (US$34 billion), agriculture, forestry and fishing (US$9 billion) and households not paying or underpaying domestic workers held in forced labour (US$8 billion).

Supply Chains Put Under Scrutiny

Federal justice minister Michael Keenan spoke this week of the formation of a Supply Chains Working Group, which will examine ways to overcome exploitative practices in the production of goods and services. The government is developing a National Action Plan to Combat Human Trafficking and Slavery, to be launched in coming months.

The working group has the challenge of tackling labour and human rights abuses in the supply chain of goods imported into Australia. The composition of the group will be critical to its success. Ideally, it will include representatives of government, industry bodies, businesses and investment funds, as well as members with academic and civil society backgrounds.

The Catalyst Australia report identified that a common obstacle to improving labour and human rights in supply chains involves stakeholders going their own way. Distinctive partnerships are pivotal to an effective response. Flagging concerns, consulting (local) experts and expanding existing knowledge are essential elements of such a response.

What Can We Do To End Abuses?

While active government involvement through legally enforceable standards is desirable, merely having laws against labour exploitation does not stop abuses. Many abuses occur outside legal frameworks, such as in the informal economy.

Increasing global co-ordination can cause discrepancies between proposed measures and their local effect, whether through legislation or self-regulation. This underlines the need for closer alignment of initiatives and partnerships at all levels.

Proposed measures should avoid a “one size fits all” approach. Solutions require pragmatic mapping of the local landscape and the issue, ongoing dialogue to see which stakeholders are on board, who can be influenced and which approaches best suit the country and industry context. Examples of sector and country-specific approaches can provide useful guidance, but only when these suit particular circumstances do they drive improvement and have maximum impact.

It is important to note that labour and human rights risks are significantly reduced where workers are allowed to organise freely and have representative trade unions. Consequently, any stakeholder who is serious about tackling these issues must be serious about supporting a free trade union movement and be willing to engage in continuing worker dialogue.

Finally, due diligence must include responsibility for human rights. Companies often narrowly define due diligence as economic and reputational risk. By scrutinising potential business partners in advance, the notion of business responsibility takes a precautionary turn.

We need to shift from merely auditing existing activities, towards promoting, protecting and advancing labour and human rights. In this way businesses can help minimise abuses and play a transformative role in all regions where they operate.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Read the original article.

About the Author

Martijn Boersma is a Researcher in Corporate Governance at University of Technology, Sydney. While obtaining a cum laude master’s degree in sociology and a master’s degree in archaeology from the University of Amsterdam, Martijn specialised in studying gender aspects of contemporary and past societies. Professionally, throughout his career with Greenpeace International in Amsterdam, his greatest interest has been the socio-economic factors of global campaign work. Disclosure Statement: Martijn Boersma works for Catalyst Australia.

Martijn Boersma is a Researcher in Corporate Governance at University of Technology, Sydney. While obtaining a cum laude master’s degree in sociology and a master’s degree in archaeology from the University of Amsterdam, Martijn specialised in studying gender aspects of contemporary and past societies. Professionally, throughout his career with Greenpeace International in Amsterdam, his greatest interest has been the socio-economic factors of global campaign work. Disclosure Statement: Martijn Boersma works for Catalyst Australia.

Recommended book:

Humanizing the Economy: Co-operatives in the Age of Capital

by John Restakis.

Highlighting the hopes and struggles of everyday people seeking to make their world a better place, Humanizing the Economy is essential reading for anyone who cares about the reform of economics, globalization, and social justice. It shows how cooperative models for economic and social development can create a more equitable, just, and humane future. Its future as an alternative to corporate capitalism is explored through a wide range of real-world example. With over eight hundred million members in eighty-five countries and a long history linking economic to social values, the cooperative movement is the most powerful grassroots movement in the world.

Highlighting the hopes and struggles of everyday people seeking to make their world a better place, Humanizing the Economy is essential reading for anyone who cares about the reform of economics, globalization, and social justice. It shows how cooperative models for economic and social development can create a more equitable, just, and humane future. Its future as an alternative to corporate capitalism is explored through a wide range of real-world example. With over eight hundred million members in eighty-five countries and a long history linking economic to social values, the cooperative movement is the most powerful grassroots movement in the world.

Click here for more info and/or to order this book on Amazon.