The notion of a “job for life” has ceased to exist for most workers in the UK. Companies are shifting the burden of earnings risk to the employee, increasing their use of zero-hours contracts. Depending on your political standpoint, this is either a logical response to the demands of fiercely competitive globalisation, or a way of exploiting workers at the more vulnerable end of the job market.

A growing feature of the “gig economy”, zero-hours contracts represent a significant change in the employment relationship as they guarantee neither work nor pay.

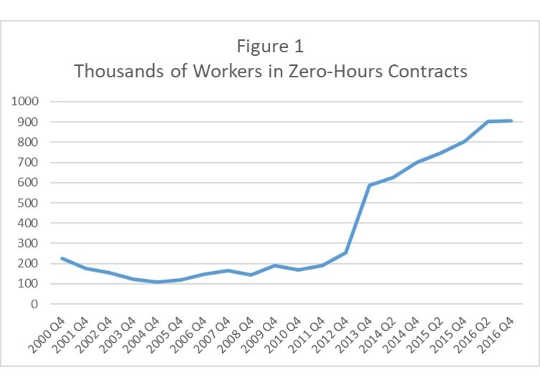

In December 2016, the UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) reported that over 900,000 workers are employed on zero-hours contracts – an increase of over 100,000 over the year, as shown in the table below.

The dramatic rise in zero-hours contracts in the UK. Keith Bender, CC BY

The dramatic rise in zero-hours contracts in the UK. Keith Bender, CC BY

The political importance of this phenomenon is reflected in both the Conservative and Labour party manifestos for the 2017 general election. The Conservative manifesto plans to give more “rights and protections” to those in the gig economy, while the Labour manifesto argues for an end to zero-hours contracts.

March of globalisation

After World War II, companies counted on stable employer-employee relationships whereby workers and firms made formal or informal contracts rather than rely on the market solely to match workers and companies.

Because they were more financially vulnerable to changes in income, workers embraced this arrangement that fostered security – their earnings were assured. And as it encouraged workers to stick around, companies enjoyed the benefits too, since they could maximise profits by attracting, retaining and training workers by providing contracts that reduced worker uncertainty over good and bad times.

But recently, precarious contracts have helped to erode the concept of a job for life, leaving workers exposed to insecurities in terms of their hours and earnings.

While zero-hours workers have the same statutory rights as other employees, there are legal issues around the definition of an employee and worker that complicate which rights are guaranteed. While some may not care about this, workers with dependants and rent or mortgages to pay are not likely to embrace uncertain pay and conditions.

For employers, the flexibility afforded by such contracts is a huge benefit for companies with variable labour demand, since they prefer a workforce that is available when needed, but not costly in periods of slack demand.

Although this flexibility may suit some workers, it is unclear whether most workers would benefit. For example, ONS data show that a third of those on zero-hours contracts want to change jobs or want more hours, compared to fewer than 10% of those employed on other kinds of contracts.

Yet the European Commission established a policy of “flexicurity” in 2007, whereby countries were directed to develop policies encouraging flexible employment contracts. While limiting job security, countries were to develop policies to help people find jobs easily, enhancing employment security. The EU flexicurity policy was motivated by the challenges of globalisation and the increasing need for firms to adapt to fast-moving changes in competition.

Health and well-being

The casualisation of employment relationships brings uncertainty to workers. For many, these contracts generate greater levels of low-grade stress than traditional contracts. This low-grade but constant stress leads to another, much less-studied and unintended consequence of zero-hours contracts: their impact on worker health.

This was the focus of our recent study, which tracked 2,300 initially healthy British workers for 17 years to see how often they found themselves in traditional or flexible contracts and whether the proportion of time spent in such contracts had any effect on their health.

Health was measured in a number of ways – a subjective opinion about overall health as well as self-reports of any health issues.

The results are striking and consistent. We found that for every measure of health we examined, the longer a worker spent in a flexible contract, the more likely they would fall ill – at a much higher rate than a worker in a permanent contract.

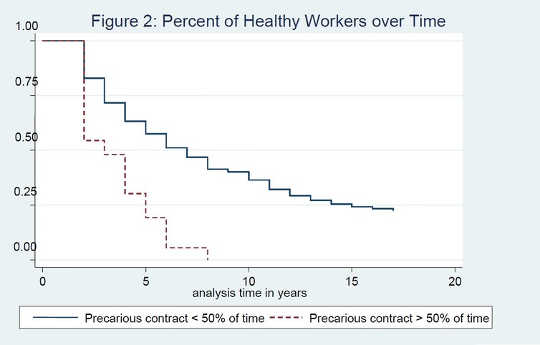

As the table below shows, by the eighth year of employment, all workers who had been in flexible contracts for at least 50% of the time experienced a fall in their overall health.

The decline in health of workers on zero-hours contracts. Keith Bender, CC BY

The decline in health of workers on zero-hours contracts. Keith Bender, CC BY

While this is a simple graph showing the state of health of those on flexible and permanent contracts, our paper reflects a variety of statistical tests to make sure that this pattern holds for all the health conditions we surveyed.

To give an idea of the correlation between zero-hours contracts and health problems, we compared the long-term effects of working on zero-hours contracts to the effects of smoking (something else we measured). Our data suggested that people who spent more time working in zero hours contracts experienced half as poor overall health outcomes as those people who smoked.

The dramatic increase in zero-hours contracts is unlikely to be entirely voluntary on the workers’ side. Again, the ONS data above suggests that a third of workers want something different. Importantly, the negative effects of flexible employment on worker health can be substantial.

The public health consequences of the increase in zero-hours contracts and its long-term repercussions on the health of the working population may outweigh the short-run profit considerations of employers. Therefore, governments should revisit policies that promote the extra flexibility if it comes with a hefty price tag of increased public health expenditure and lost productivity.

![]() Without factoring in this further cost of zero-hour contracts, there could be unintended consequences for society which are detrimental to productivity, and more worryingly, the health and well-being of the working population.

Without factoring in this further cost of zero-hour contracts, there could be unintended consequences for society which are detrimental to productivity, and more worryingly, the health and well-being of the working population.

About The Author

Keith Bender, SIRE Chair in Economics, University of Aberdeen and Ioannis Theodossiou, Chair in Economics, University of Aberdeen

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon