Data on aspects of fathering, including the number of stay-at-home dads is patchy in Australia. Paolo.Pace

Data on aspects of fathering, including the number of stay-at-home dads is patchy in Australia. Paolo.Pace

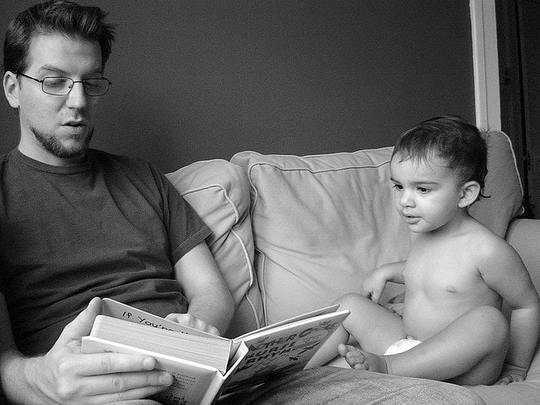

The picture of a dad with a toddler in his arms happily waving as mum heads off to work is attractive – it suggests a more equal, sharing and caring type of world.

But is this a reality of family life or simply media myth making?

Last week, the Guardian’s headline “Stay-at-home dads on the up: one in seven fathers are main childcarers” seemed to be announcing a major shift in gender roles.

The survey being quoted was from Aviva, one of the biggest insurers in the United Kingdom, which asked 2000 parents about child care.

Of the respondents, a quarter of the dads (26%) either gave up work or reduced working hours after the birth of children, and 44% said they regularly looked after children while their partner worked.

But the big news was how many dads were taking over from mums.

When asked “What is the gender of the person in your household who carries out the majority of childcare?” a whopping 14% pointed to the dad. That meant, Aviva figured, that 1.4 million men in the United Kingdom are now stay-at-home-dads.

New-age fathering and money were equal drivers of the change.

Almost half of stay-at-home-dads (43%) said they felt “lucky” to have the opportunity to spend more time with their kids, while 46% of families said their decision allowed the main income earner, the mother, to keep working.

Could these figures translate to Australian families? Possibly.

In 2010, adults who were not in the labour force were asked why they were not looking for work. Out of the 168,000 who gave their main reason as looking after children 8,500 (5%) were men.

If the pattern in Australia is similar to was recorded in Aviva’s UK survey and as many men again are the main caregiver because their wives are earning more, then Australia would have around 10% stay-at-home dads.

While this figure is below the United Kingdom (14%), it still shows a promising trend.

One in ten families where dad does the caring is hardly the 50-50 implied by “equal care”, but it still may reflect an important change.

The trouble is, relying on private businesses to measure change and media to interpret the figures leaves a lot of room for exaggeration.

Only last April the Guardian ran a very similar story, again quoting as fact, a survey from Aviva.

The headline last year was even more dramatic “Tenfold rise in stay-at-home fathers in 10 years”.

In that story, just 18 months ago, the number of stay-at-home dads was reported as 600,000 or 6% of the respondents.

After a tenfold rise in ten years, it seems that an extra 800,000 families switched roles in just 18 months, more than doubling the percentage of homes where dad does the most caring.

So perhaps there is a major change afoot. Certainly, the way parents arrange care of their children is an important social question. That is reason enough to ask for accurate and regular measures of parenting.

But in Australia, we are some way from having good data. We track mothers and mothering quite well but our data on fathers and fathering is patchy.

This means judging change is still guesswork.

Our basic record of births, for example, lists the mother’s age, smoking status and Aboriginality but contains nothing about fathers. And our major national study of children interviews mothers about every aspect of the child’s life but leaves forms on some topics for fathers to complete.

In the lead up to the introduction of paid paternity leave next year, getting the records straight on how many fathers and mothers there are, and then asking fathers as well as mothers who does what, will help us track important social changes in family life.![]()

About The Author

Richard Fletcher, Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Health , University of Newcastle

Este artículo fue publicado originalmente en The Conversation. Lea el original.

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon