Image by Gerd Altmann

Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom. — ROLLO MAY

The singular and most important idea that will help us stay calm in an emergency — or at any other time — is that we have a choice.

It often doesn’t feel like we have a choice. Something happens, we get rear-ended on the highway, and we are quick to anger. We think the guy that hit us made us angry! That happens so fast in our minds that we link the event (being hit) to the consequence (our anger).

In other words, we think being hit caused our anger.

That is a troubling statement, for it implies that we have no choice in the matter. Something happens, and I respond in one way; something happens again, and I must respond again and again in the same way.

This assumption of cause and effect is built into our language:

- My kids make me mad.

- My girlfriend (or boyfriend) drives me crazy.

- The traffic makes me impatient.

When we use and believe this language, we set ourselves up to be ping-pong balls in life, reacting to one event after another. We become like Pavlov’s dogs, salivating every time the bell rings and saying to ourselves, “It’s that darn bell!”

Intuitively, we know that is not true. Intuitively, we know that we can influence our thinking and choose how to act. For example, if a motorist hits our car, our immediate reaction might be fear and shock. Something unexpected and dangerous has happened.

If we are physically unhurt, what happens next? Do we become angry, blaming the other driver for doing something wrong? Do we jump out to see if the other driver is okay, since they might be hurt? Do we restore our own sense of calm and simply be grateful it wasn’t more serious? We have a choice.

What is behind the choices we make? A quick illustration from the firefighter world:

Three firefighters respond to a cardiac arrest and perform CPR. Although they work the code by the book, the patient doesn’t recover. Our first firefighter, an experienced paramedic, comforts the family by saying (and believing), “We did everything we could.”

The second firefighter, a brand-new EMT, is upset at losing their first cardiac arrest patient. The person blames themselves and their training, thinking, This is not the way it worked in class! The third firefighter, the veteran chief, walks away depressed and discouraged, thinking, I can’t attend one more death, CPR never works…

The cardiac arrest is the same; the CPR techniques and results are the same. So what caused the three different reactions? The diverse beliefs and thinking of each person.

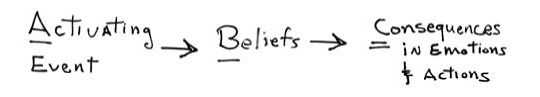

To be nerdy for a moment, here is an “ABC” diagram of what happened:

The activating event is A; this is anything that happens that gets our attention. This is filtered by our beliefs (or B), which include our history, experiences, and worldview. Finally, the consequence (or C) is how we respond as a result: what we choose to feel and do.

Obviously, we are not in control of “A,” the activating events. Stuff happens. The pager goes off in the middle of the night. Yet we can control our beliefs and attitude, our world-view.

We can also recognize difficult emotions and choose how to manage them. Fear doesn’t have to become anger and blame. Failure doesn’t have to lead to self-doubt and discouragement. We can think: The driver behind me just made a mistake. I’ve done it before myself. This is inconvenient, but it is not a tragedy. Or: CPR works 10 percent of the time in the field. Its’ not perfect, but its ’ the best we have.

Our beliefs influence how we understand and respond to events. So if our responses are unhelpful, if we lose our cool, if difficulties invariably cause eruptions of anger, then we can adjust our thinking and beliefs and change how we respond in order to be more effective, helpful, and happier.

Stop, Challenge, and Choose

First, we have to acknowledge that our minds are not fact-finding, truth-telling computers. Instead, they are full of beliefs, assumptions, prejudices, stories, and ways to successfully navigate our worlds. In a phrase, we are all graduates from the University of Making Stuff Up. We get a couple of data points, and we generalize: Hah! This is the way things are!

Many of those beliefs, no matter how “off” they might be, go unchallenged throughout our lives.

To respond more effectively, then, our goal should be to continually examine our beliefs, test them against reality, and make sure they are accurate. In other words, to quit making stuff up!

That is the theory, and here is a tool for doing so that is called “Stop, Challenge, and Choose.”

STOP: Whenever an “activating event” causes you to feel upset, stressed, or any negative emotion, stop. Either physically stop or get off the roller coaster of thoughts and feelings in your mind. Next, breathe and calm down. Try the “square breathing”:

- Two seconds: inhale

- Two seconds: hold your breath

- Two seconds: exhale

- Two seconds: hold

- Repeat for four to six breaths

CHALLENGE: Ask yourself, What am I making up? What belief is causing me to be upset or stressed? This can be hard work, but it is vital to understand what belief is causing your stress and upset.

Dr. Maxie Maultsby, the late American psychiatrist, suggested the following criteria for examining our beliefs (or what we might be making up):

- Is my belief aligned with the facts?

- Is it in my best short- and long-term interests?

- Does it avoid unnecessary conflict with others?

- Will my response help me feel the way I want to feel?

CHOOSE: Choose a belief that is based on facts, that is in your best interests, that avoids unnecessary conflict, and that makes you feel the way you want to feel.

Once you’ve practiced Stop, Challenge, and Choose a few times, it becomes an automatic way to think, and it can take two minutes to apply.

As a firefighter, I use this during almost every call I go on. When I’m surrounded by upset people, and I can feel the tug of adrenaline, I stop, control my breathing, and challenge the thought, Everyone is panicking; therefore, I should panic, too! To calm myself, I often choose a mantra — like “This is not my emergency” or “Go slow to go fast.”

When I consciously use this skill, I can show up the way I want to show up. This is the outcome we’re looking for: to match our actions with what’s needed in each moment or with the person we want to be.

©2020 by Hersch Wilson. All Rights Reserved.

Excerpted with permission of the publisher.

Publisher: New World Library.

Article Source

Firefighter Zen: A Field Guide to Thriving in Tough Times

by Hersch Wilson

“Be brave. Be kind. Fight fires.” That’s the motto of firefighters, like Hersch Wilson, who spend their lives walking toward, rather than away from, danger and suffering. As in Zen practice, firefighters are trained to be fully in the moment and present to each heartbeat, each life at hand. In this unique collection of true stories and practical wisdom, Hersch Wilson shares the Zen-like techniques that allow people like him to stay grounded while navigating danger, comforting others, and coping with their personal response to each crisis. Firefighter Zen is an invaluable guide to meeting every day with your best calm, resilient, and optimistic self.

“Be brave. Be kind. Fight fires.” That’s the motto of firefighters, like Hersch Wilson, who spend their lives walking toward, rather than away from, danger and suffering. As in Zen practice, firefighters are trained to be fully in the moment and present to each heartbeat, each life at hand. In this unique collection of true stories and practical wisdom, Hersch Wilson shares the Zen-like techniques that allow people like him to stay grounded while navigating danger, comforting others, and coping with their personal response to each crisis. Firefighter Zen is an invaluable guide to meeting every day with your best calm, resilient, and optimistic self.

For more info, or to order this book, click here. (Also available as a Kindle edition and as an Audiobook.)

About the Author

Hersch Wilson is a thirty-year veteran volunteer firefighter-EMT with the Hondo Fire Department in Santa Fe County, New Mexico. He also writes a monthly column on dogs for the Santa Fe New Mexican.

Hersch Wilson is a thirty-year veteran volunteer firefighter-EMT with the Hondo Fire Department in Santa Fe County, New Mexico. He also writes a monthly column on dogs for the Santa Fe New Mexican.