I’m going to take a dip into my own past in order to shine a light on psychiatry’s rear-view mirror. As a child, I suffered from countless sore throats and ear infections, and was treated by a neighborhood doctor as well as my father, who was a doctor and a surgeon.

When I was about five years old, my father offered to drive me to school one day. He had never done this before—and some part of my child’s brain must have wondered why he would drive me to school when we lived right across the street from it. But I’d always loved riding in cars with my dad, so I agreed.

I was excited as I jumped into the back seat of his steel-gray Buick sedan. He pulled out of the driveway and drove down the block. At the corner of our block, we made a right turn onto the main local avenue and drove at least twenty blocks away from the school. When I asked where we were going, my father told me he had to make a stop first.

Suddenly he pulled up and parked right in front of a big hospital. Because my father was a surgeon, I’d had the experience of waiting in the car while he made a post-op call to see one of his patients, something that was done much more often back in those days. But this time, he told me to come with him. Of course I did, but I began to feel anxious immediately as I trotted along, trying to keep up with his long stride.

We went through the main entrance of the hospital. My heart was already starting to pound when a scary-looking nurse with gray hair grabbed me by both arms, lifting me right off the ground. My father said sternly, “Take it easy,” but she already had me in her grip and whisked me away.

The next thing I remember, I was put in what looked like a cold white bedroom, where someone in white clothes took blood from my arm. Of course I was terrified. Why was this happening? Where was my father, and why had he brought me here? What would my mother say when she found out?

I remembered that she hadn’t given me any breakfast that morning. Now, of course, I know why, but at the time it just added to my feeling that nothing was normal that day. They put me onto a hospital gurney, like a tall bed on rattling wheels, and I was whisked down a long hall to an operating room. The same gray-haired nurse with the mean face was there. As she leaned over me, terror took over. She put a mask over my mouth, and I started seeing all sorts of colors.

The next thing I knew, I was in a bed. Someone was giving me ice water to drink. As I recall, I was quite calm. My father and mother were both in the room. My father told me that my tonsils and adenoids, which had been causing so many sore throats and earaches, had just been removed. I would not be sick anymore, he said. I must admit I was quite happy.

My father told me that a doctor our whole family knew—an ear, nose, and throat specialist—had been the one to operate. He also told me that he himself had been in the operating room the whole time, and told me that I had been brave. I would be going home soon, he said. I would not have to stay overnight like most patients who had a tonsillectomy, because he was a doctor, he could look after me at home. This made me even happier.

I remember feeling really lucky. But just as we were leaving the hospital room, that gray-haired nurse came in to say goodbye, and I felt the same sense of terror wash over me.

We left and got back into the Buick. My father was at the wheel, as before, but this time I sat in the back seat, right next to my mother. I remember her telling me I could eat plenty of ice cream to make my throat feel better. The terrible, scary day was over, or so I thought. But it wasn’t actually gone from my mind.

Memories and Flashbacks

Fast-forward to my teen and adult years: My career plans started to center on becoming a doctor, following in my father’s and my uncle’s footsteps. For several years after having my tonsils removed, I continued to have memories and flashbacks of that terrifying moment when the nurse grabbed me as we entered the hospital.

It’s important to point out, too, that I never had any bad feelings or thoughts about my surgeon father. He had figured out what I needed, and did his best to solve a medical problem for his only son.

Those were different times. Parenting styles change like anything else. A parent today would handle this kind of situation differently, offering explanations and reassurances about what was going to take place, perhaps staying with his child for as long as he could. But the thinking back then was just to get things over with.

I don’t think walking me through the whole procedure until I understood it would have been in my father’s thoughts at that time, and I don’t blame him for that. It’s not easy to explain hospitals and surgery to a five- or six-year-old, and he probably thought he was sparing me from fears and worries.

Also, in truth, the ride to the hospital was not all that bad. Being in a car with my father was always a treat. My anxiety and subsequent terror really came from the way that one nurse had handled the situation. That’s what really scared me. I think if she had said, “Hi there, how are you? Let me show you around,” or offered me a toy—as is done today when you bring a tot into an emergency room—I would have felt reassured and comforted, and been able to handle whatever came next.

As a psychiatrist looking back on this experience, the question that interests me is what, if any, lasting trauma occurred from it? For a while I was hypersensitive even to hearing about hospitals, or people going into the hospital—and given my father’s profession, it was frequently a topic of family conversations. I also had recurring visions of this nurse grabbing me inside the hospital doorway, of her putting the anesthesia mask over my face.

I thought this through at about age eleven, when I made the decision to become a doctor. I remember making the clear decision that I could let go of these fears. Nothing bad had happened to me, after all. I was fine.

Whether I already had some early inkling of what would years later become my LPA technique, I don’t know. [LPA = Learning, Philosophizing, and Action] But I do remember thinking, “I don’t have to be scared of this.” And I also know I made a complete self-recovery. At least I thought so, until my first year as a psychiatric resident, after I’d finished medical school.

Dredging Up Old Memories

In the first year of training, which was mainly inpatient psychiatry, learning to treat patients, attending daily lectures, and having individual supervision, we also had a weekly group therapy session for all the trainees. This included residents from all the years of training, so it was a pretty big group, run by two psychiatrists. Part of the experience was not only learning about the group therapy process, but having a chance to discuss the stresses and problems of being a young doctor, and the emotional and practical issues we might encounter in treating patients. All in all, the intentions were good. It was not a bad thing to be able to talk like this.

But as time moved along, those sessions took on a different tone. The psychiatrists who led the group began to probe deeper into our personal lives, something I didn’t think was right at the time and still think was inappropriate. We hadn’t asked to be patients. In this case, we were being “psychoanalyzed”—you might even say scrutinized— in front of our peers, and it was not exactly comfortable.

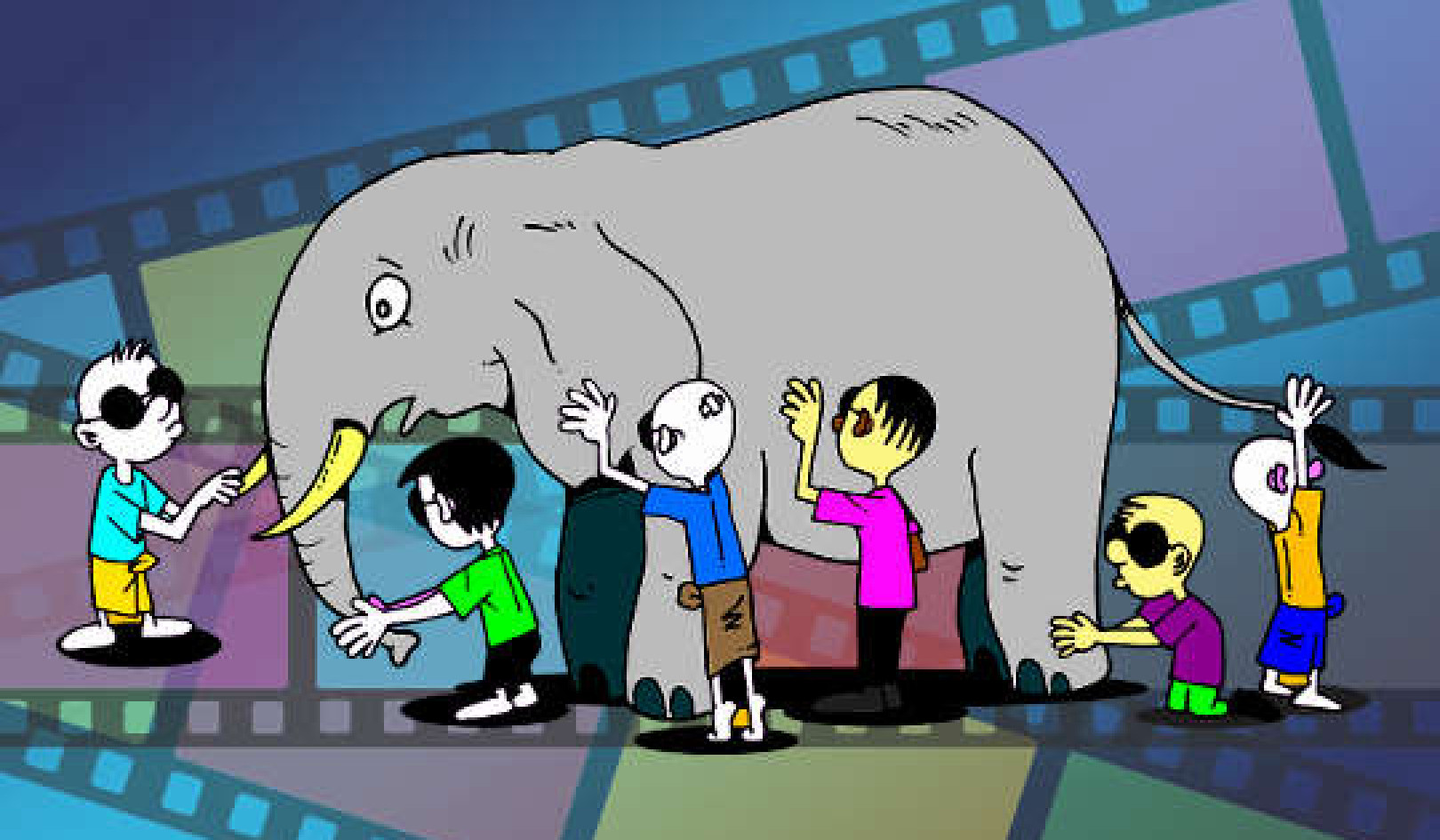

Each of us was asked to describe a frightening situation in our lives. Naturally, I referred back to my early trauma over that tonsillectomy. It was a memory, far in the past. But the two psychiatrists seized on it. They focused on my father, framing his behavior as thoughtless and even brutal—didn’t I see how he had tricked me into going to the hospital? Didn’t I realize I’d been manipulated, a child victimized by false pretenses?

Well, no, I said. Because I honestly didn’t. My response was protective of my father. I took care to point out what a good father he was. I told the group and the two psychiatrists that every Wednesday afternoon, after he finished his surgery, he’d take me out of school an hour early and we’d go to a movie, a museum, a boat show, a car show or the planetarium. This started at around age five and went on until I was twelve, when I developed my own social life and could no longer leave school early.

I also told them my father had bought me my first car, paid for my college, covered my medical school tuition. And he’d been my inspiration for choosing a medical career in the first place. He was my rock.

There were lots of other good things my father did as I grew up. But the psychiatrists did not listen. They countered every positive thing I said about him, insisting that it was “defensiveness,” and that I was idealizing the man.

It was a no-win situation. A few of my fellow trainees began laughing at the way the psychiatrists kept pursuing this, but other than that, no one pointed out how these views were not even based on medically documented fact, but on personal theories. I remember bringing that up. One of the psychiatrists was so offended that he claimed these “theories,” developed by great thinkers in the field (i.e., Freud and his followers) were more accurate than mathematics or physics. Didn’t I know that? Half the group was laughing at his assertion, but we were trainees, after all. We were putty in their hands.

The negative thoughts these doctors were aiming to plant in my mind, and their attempts to undermine a great relationship, certainly had an effect on me. But I doubt it was the effect they’d intended. Instead of doubting myself and my feelings about my father, I began to doubt their approach.

I should thank these two, actually, as they gave me a strong early start in avoiding that type of therapy. I was absolutely struck by how undermining it was. It was a therapeutic approach not focused on problem solving, but on creating more problems—by sowing the seeds of emotional dissent, and dredging up buried events from the past with their interpretations being guesswork at best.

My father was still alive and active in his surgical practice at that time, so I ran by him how these training psychiatrists were interpreting my tonsillectomy. He set me straight on several points. While we were in the car, he did tell I was going to a hospital to get my sore throats and earaches fixed and that a doctor I already knew would do the job—something I’d entirely forgotten. He also told me clearly that he would be with me the whole time, as he was a senior doctor at the hospital. And he reported that he had been furious at that nurse, whom he’d never felt good about.

I was actually somewhat relieved to learn that he had informed me of what was going to happen. I knew my father was telling the truth, because that’s the kind of person he was.

A Tale of Two Therapies

Unfortunately, so many people who seek help through therapy are met with that same kind of unproductive approach. In comparison, let’s look at how one of my brilliant psychiatric colleagues, a down-to-earth, pragmatic practitioner of CBT (Cognitive Behavior Therapy), and how she responded.

When I recounted that same story of the tonsillectomy, she did not fault my father, or argue with any kind of defensive response on my part. Instead, she made the more accurate observation that my teenage self could have benefited from a better understanding of the trauma I’d suffered, with recurrent images of that nurse. It was the nurse who had frightened me as a young child, with her startling face and her harsh bedside manner. Had the psychiatrists running that session listened a little more carefully, they might have been able to focus more on that.

What upset my colleague (and me) most is that so many therapists, including psychiatrists, psychologists, and the whole band of social workers and other practitioners, still continue to worship psychoanalytic notions put forth more than a century ago. The widespread allegiance to these antiquated and cult-like philosophies interferes with simply trying to improve patients’ lives as simply and quickly as possible. No other field of medicine or health care can boast of this absurdity.

From Talking to the Pharmacy... or to Problem Solving

This stuff goes on and on. That therapeutic process can take many years—or for some psychoanalytic patients in the Woody Allen-movie mold, many decades—at tremendous expense, and let us not forget that expense is a key factor. Sometimes, in fact, you might get worse in reaction to certain unacceptable ideas your psychiatrist or therapist is insinuating. If you are seeing a psychiatrist, he or she might prescribe a medication as you fail to improve.

If you see a non-MD therapist, he or she may refer you to a prescribing psychiatrist or a primary care doctor to prescribe medications. As you continue to unravel these absurdities and unconscious configurations, it gets more and more costly and frustrating.

All too often, the patient/client eventually makes some accurate assessment that the real problem is not being addressed, but is either assured that he is “getting there” or accused of “resisting the process.” According to a Harvard study some years ago, over 50 percent of psychiatric patients will drop out of traditional talk therapy treatment, even though they claim to like their therapists.

But in a CBT program, or using my LPA technique, the process is entirely different. It’s short, focused, and goal-oriented. Working with your therapist, you identify the mistaken ideas and distorted thoughts that led to some type of distress. Then you challenge these thoughts and exchange them for a more realistic perspective. This process allows you to develop and learn a new and better set of responses to the old set of problems—and those responses will continue to work when your treatment is over.

The goal is not to meander all over your brain, probing the outdated beliefs and fantasies that a therapist is projecting onto you. The goal is to thoughtfully learn or relearn new techniques and perspectives to get your problem solved so you can find freedom fast.

Copyright 2018 by Dr. Robert London.

Published by Kettlehole Publishing, LLC

Article Source

Find Freedom Fast: Short-Term Therapy That Works

by Robert T. London M.D. Say Goodbye to Anxiety, Phobias, PTSD, and Insomnia. Find Freedom Fast is a revolutionary, 21st-century book that demonstrates how to quickly manage commonly seen mental health problems like anxiety, phobias, PTSD, and insomnia with less long-term therapy and fewer or no medications.

Say Goodbye to Anxiety, Phobias, PTSD, and Insomnia. Find Freedom Fast is a revolutionary, 21st-century book that demonstrates how to quickly manage commonly seen mental health problems like anxiety, phobias, PTSD, and insomnia with less long-term therapy and fewer or no medications.

Click here for more info and/or to order this paperback book. Also available in a Kindle edition.

About the Author

Dr. London has been a practicing physician/psychiatrist for four decades. For 20 years, he developed and ran the short-term psychotherapy unit at the NYU Langone Medical Center, where he specialized and developed numerous short-term cognitive therapy techniques. He also offers his expertise as a consulting psychiatrist. In the 1970s, Dr. London was host of his own consumer-oriented health care radio program, which was syndicated nationally. In the 1980s, he created “Evening with the Doctors,” a three-hour town hall style meeting for nonmedical audiences—the forerunner to today’s TV show “The Doctors.” For more info, visit www.findfreedomfast.com

Dr. London has been a practicing physician/psychiatrist for four decades. For 20 years, he developed and ran the short-term psychotherapy unit at the NYU Langone Medical Center, where he specialized and developed numerous short-term cognitive therapy techniques. He also offers his expertise as a consulting psychiatrist. In the 1970s, Dr. London was host of his own consumer-oriented health care radio program, which was syndicated nationally. In the 1980s, he created “Evening with the Doctors,” a three-hour town hall style meeting for nonmedical audiences—the forerunner to today’s TV show “The Doctors.” For more info, visit www.findfreedomfast.com

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon