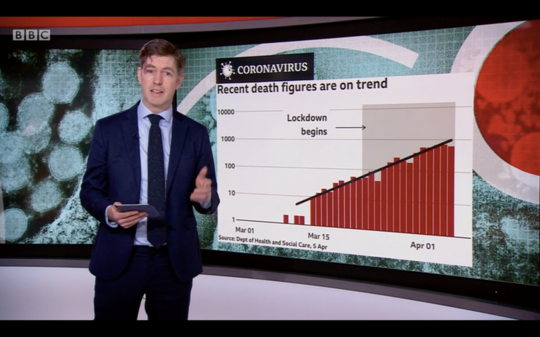

A BBC report on daily death tolls. But does it really help? BBC

A BBC report on daily death tolls. But does it really help? BBC

People are currently being bombarded with reports of the daily death toll from coronavirus. Practically every news website and channel displays the number prominently at all times. These figures provide important data to statisticians but what effect are they having on the rest of us?

Daily death figures allow experts to more accurately estimate the spread of the virus because they provide an objective benchmark that corrects for international differences in testing and reporting. They provide useful feedback to help gauge the impact of protective measures as we attempt to “flatten the curve”. But do they benefit the general public?

An obvious direct effect for the rest of us is that these figures remind us of the dreadful outcomes that result from breaching the guidance on handwashing and physical distancing. Rational decision-making is informed by two factors: risk and reward. Reporting the daily death toll reminds us to behave prudently. We remember that there is a meaningful risk of a tragically negative reward if we don’t.

But there are also less obvious – and less conscious – effects. In recent decades, experimental social psychologists have tested what happens when we prompt people to think about death.

What motivated their research is termed Terror Management Theory (TMT). It is rooted in theories of Sigmund Freud and philosopher Søren Kierkegaard and was given coherent expression in Ernest Becker’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book Denial of Death. The premise is that we have evolved elaborate mechanisms to mitigate the existential concerns resulting from the awareness that we will someday suffer physical death. The practical implication is that our motivations (and hence our real-world behaviours) can change when we are confronted with thoughts of death.

Experiments in the TMT field show that prompting death-related thoughts can increase risky behaviour. That is quite contrary to the rational risk-reward calculus articulated above. The logic is that risk-taking can be a source of self-esteem and one common way of coping with the inescapable threat of death is to bolster our self-esteem. Hence, reminders that smoking kills can actually increase smokers’ cravings and reminding drivers of the risk of death can increase speeding for some.

Gambling with life

It’s not just the fact of mentioning death that plays a part, either. The high numbers involved in these particular circumstances may also have an independent effect.

A set of studies made participants responsible for managing a hypothetical epidemic that would kill 600 people. Participants could choose a program that would result in 400 deaths or another that offered a one in three chance of saving everyone and a two in three chance of letting all 600 die. Participants from countries that had experienced several disasters in which hundreds of people had died (relative to those from countries where such disasters were extremely rare) were more willing to accept 400 deaths.

Another study from the same paper has even greater relevance: it found that participants were more willing to accept 400 deaths after reading a series of headlines in which a high (versus low) number of deaths were reported.

In short, when you encounter news that hundreds of people just like your neighbours have died in the past day, there are consequences for your judgement and decision-making. You are unlikely to be conscious of some of these consequences and, contrary to what the media and officials would wish, they might make you sensitive to the risks that we now face.

So what is a responsible editor to do? TMT suggests how mortality statistics might be presented without inducing unconscious effects. The key is that death is less threatening when it is explicitly linked to values we admire. Heroes typically embody the traits that we would like to see continue into future generations, and so relating thoughts of death to heroism can serve as a buffer against existential concerns.

Experiments show that prompting thoughts of heroes and heroism reduces the tendency to fixate on death. For instance, after having been prompted to think about death, participants who had earlier read a case of heroic self-sacrifice (saving a child from a burning car) were substantially less likely than others to form death-related words in a word-completion task. They were more likely to complete the puzzle C O F F _ _ as COFFEE whereas people asked to think about death but not shown a case of heroic self-sacrifice were more likely to complete it as COFFIN.

What are the practical implications of this? Well, headlines that explicitly mention the heroism of NHS workers alongside death tolls would be expected to allay mortality concerns. In this way, the communication of death-related information might avoid some of the negative biases, attitudes and behaviours instilled by mortality reminders.

We are living in exceptional times, as daily news reports remind us. There is an onus on the media to ensure that messaging doesn’t make matters worse.![]()

About The Author

David Comerford, Program Director, MSc Behavioural Science, University of Stirling and Simon McCabe, Lecturer in Management Work and Organisation, University of Stirling

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Related Books:

Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones

by James Clear

Atomic Habits provides practical advice for developing good habits and breaking bad ones, based on scientific research on behavior change.

Click for more info or to order

The Four Tendencies: The Indispensable Personality Profiles That Reveal How to Make Your Life Better (and Other People's Lives Better, Too)

by Gretchen Rubin

The Four Tendencies identifies four personality types and explains how understanding your own tendencies can help you improve your relationships, work habits, and overall happiness.

Click for more info or to order

Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don't Know

by Adam Grant

Think Again explores how people can change their minds and attitudes, and offers strategies for improving critical thinking and decision making.

Click for more info or to order

The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma

by Bessel van der Kolk

The Body Keeps the Score discusses the connection between trauma and physical health, and offers insights into how trauma can be treated and healed.

Click for more info or to order

The Psychology of Money: Timeless lessons on wealth, greed, and happiness

by Morgan Housel

The Psychology of Money examines the ways in which our attitudes and behaviors around money can shape our financial success and overall well-being.