If a stranger offered a child free lollies in return for their picture, the parent would justifiably be angry. When this occurs on Facebook, they may not even realise it’s happening. ![]()

There was outrage after a recent report in The Australian suggesting that the social media company can identify when young people feel emotions like “anxious”, “nervous” or “stupid”. Although Facebook has denied offering tools to target users based on their feelings, the fact is that a variety of brands have been advertising to young people online for many years.

We’re all familiar with traditional print and television advertising, but persuasion is harder for children and parents to detect online. From using cartoon characters to embody the brand, to games that combine advertising with interactive content (“advergames”), kids are exposed to a pervasive ecosystem of marketing on social media.

The blurring of the line between advertising, entertainment and socialising has never been greater, or more difficult to fight.

Kids are vulnerable to junk food advertising

Junk food advertising aimed at both adults and children is nothing new, but research shows that young people are particularly vulnerable.

Their minds are more susceptible to persuasion, given that the part of their brain that controls impulsivity and decision-making is not always fully developed until early adulthood. As a result, children are likely to respond impulsively to interactive and attractive content.

While the issue of advertising junk food to children through television and other broadcast media gets a lot of attention, less is understood about how children are consuming such marketing online.

How brands interact online

We examined how six “high-fat-sugar-salt” food brands approached consumers at an interactive, direct and social level online in 2012 to 2013 (although the practice continues).

Analysing content on official Facebook pages, website advergames and free branded apps, we coded brand placements as primary, secondary, direct or implied brand mentions.

While the content may not be explicitly targeted at children, the colours, skill level of the games and the prizes are attractive to younger people. The responses on Facebook in particular show that young consumers often interact with these posts, sharing comments and reposting.

We found food brands being presented online and interactively in four main ways: as “the prize”, “the entertainer”, the “social enabler” and as “a person”.

1. The prize

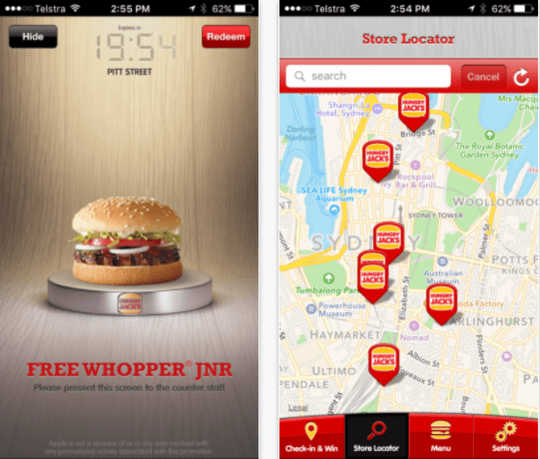

The fast food company Hungry Jack’s Shake and Win app has been offered since 2012. By “shaking” the app, it tells you, using your smartphone GPS, which Hungry Jack’s outlet is closest and where you can redeem your “free” offer or discount.

In this way, it combines several interactive elements to push the user towards immediate consumption with the brand coded as a reward.

Hungry Jack’s Shake and Win app screens captured on May 17th 2017. iTunes/Hungry Jacks

Hungry Jack’s Shake and Win app screens captured on May 17th 2017. iTunes/Hungry Jacks

2. The entertainer

Free branded video game apps or advergames are also used to engage young consumers, disguising advertising as entertainment.

In the 2012 Chupa Chups game Lol-a-Coaster (which is not currently available on the Australian iTunes store), for example, we found a lollipop appeared as part of game play up to 200 times in one minute. The game is simple to play, full of fun primary colours and sounds, and the player is socialised to associate the brand with positive emotion.

Chuck’s Lol-A-Coaster: an interactive game for Chupa Chups.

3. The social enabler

Brands often leverage Facebook’s “tagging” capability to spread their message, adding a social element.

When a company suggests that you tag your family and friends on Facebook with their favourite product flavour, for example, the young consumer is not only using the brand to connect with others, but letting the brand connect to their own Facebook network. For a brand like Pringles, this increases their reach on social media.

A post on the Pringles’ Facebook page on October 13th, 2016. Facebook/Pringles

A post on the Pringles’ Facebook page on October 13th, 2016. Facebook/Pringles

4. The person

Some brands also use a humanised character, like Chupa Chups’s Chuck, to voice the brand and post messages to consumers on Facebook.

Often this character interacts with the consumer in a very human way, asking them about their everyday lives, aspirations and fears. This creates the possibility of a long-term brand relationship and brand loyalty.

A Chupa Chups post on September 2nd, 2014 showing the character, Chuck. Facebook/Chupa Chups

A Chupa Chups post on September 2nd, 2014 showing the character, Chuck. Facebook/Chupa Chups

Brands need to clean up their act

Using Facebook, advergames and other online platforms, food marketers can create deeper relationships with kids than ever before. Going far beyond a televised advertisement, they are able to create an entire “brand ecosystem” around the child online.

The latest National Health Survey found that around one in four Australian kids aged 5-17 were overweight or obese. Food marketers promoting unhealthy options to kids online should be held to account.

In Australia, the food marketing industry is mostly self-regulating. Brands are meant to abide by a code of practice which, if breached, holds them account through a complaints-based system.

While some companies have also pledged, via an Australian Food and Grocery Council code, not to target child audiences using interactive games unless offering a healthy choice, the current system is too slow and weak to be a real deterrent. That needs to change.

While online food marketing may be cheap for the corporations, the price that society pays when it comes to issues such as childhood obesity is immeasurable.

About The Author

Teresa Davis, Associate Professor, University of Sydney. Her main research interests lie in two areas. The first is in children as consumers, of particular interest is the relationship between advertising and marketing of food. The second area is culture and consumption where her interests lies in examining 'cultures of transition' such as consumption of/in childhood and migrant groups. Related areas of research include the socio-historical analyses of culture and consumption.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Related Books:

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon