Before i was informed that I was “profoundly dyslexic,” I just thought I was stupid and too weird to cultivate friends. I often talked too much, or not at all. In school, I would get an A for creativity over a D for atrocious grammar—“excellent creative thinking,” the teacher said, “but nearly untranslatable into English.”

I was having considerable difficulty reading anything, much less a map. I had trouble telling my right from my left, I could not comprehend most directions, I was lost much of the time. Infrequently, I was given to a rather loud swearing when startled at a time and in places where such behavior was taboo. I was like an acrobat falling from tightrope to tightrope, never quite able to find a natural balance.

I often counted numbers to myself to get my grounding. The counting, quite unexpectedly, began to intensify my concentration, which brought some calm to the twisty mind. Though it originated from a sense of weakness, it gave me some strength and steadiness. It was manna from heaven for a wobbly dyslexic.

I had, for much of my life, difficulty with the waves and troughs of my speech patterns. I had not yet found the middle way. It made communication and connections quite uncomfortable and added a compulsive repetitiveness. I constantly attempted to say things clearer.

Different Brain Wiring: Seeing Life in Pictures

My brain just isn’t wired the same as that of most people. I see life in pictures. That is why it was so difficult to find the right words quickly enough to communicate well. I have to riffle through a number of images before I can tune into what is an appropriate response.

I understand much more easily if I see a photo or if someone draws a picture of what they mean. I can read a sentence and have high comprehension but an inability to repeat the words, almost a kind of paralysis, when I attempt such a task.

When someone speaks, I have to find the corresponding files and access them, which takes time to figure out what they really mean since I think very literally. I put these pictures together to come up with ideas of what to say and how to say it.

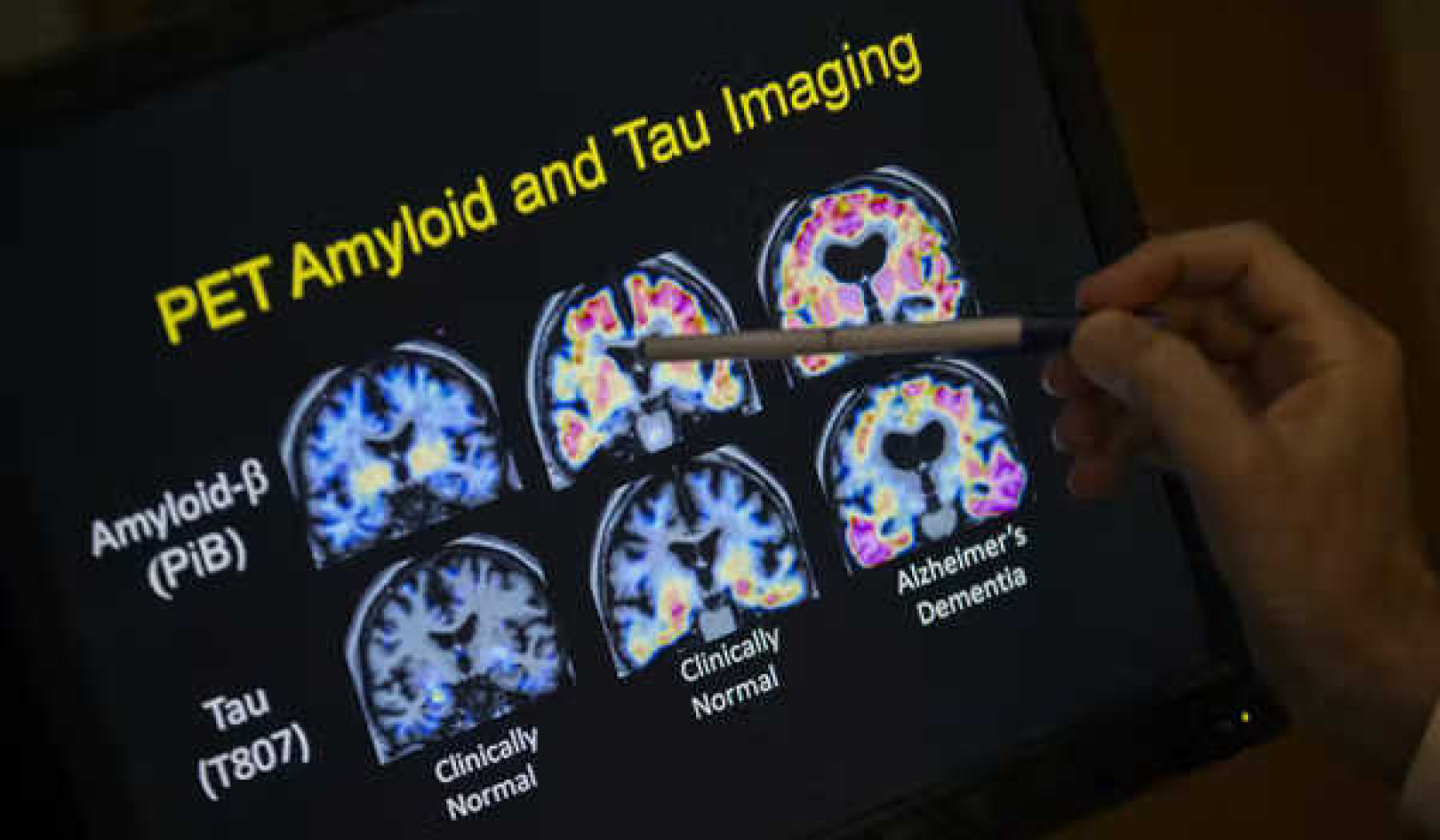

Because this process is slower than conversation, it makes me nervous or anxious, and I often don’t say exactly what I mean the first time and have to repeat myself to be clear. This anxiety is caused by an automatic overload of the amygdala region of the brain, which functions in response to stress with a “fight or flight” reaction, a “high alert” flooding the system with adrenalin.

This experience only serves to amplify feelings of tension, lack of safety, and considerable discomfort. In my case, because of the biological malfunction I was born with, I stayed on high alert longer than required. In time this can be somewhat, if not greatly, mollified by the grounding action of mindfulness and heartfulness practices.

Learning to Respond to Fears Rather Than React to Them

Getting into concentration exercises helped me evolve from reacting to old fears and anxieties to responding to them. This even extended into my dreams, as I was learning to respond to the content of the passing show of images and thoughts rather than give in to that old urge to withdraw and even hide from the mind. I was becoming less compulsively reactive.

I learned to soften my body and watch my states of mind with a bit more compassion for myself. My life was no longer an emergency.

At times I still have anxiety about the workings of my brain, but if afflictive emotions get too seductive and threaten to pull me down under the waves, I release my pushing and pulling at such thoughts and instead begin to relate to them directly on the level of sensation. Not burying the thoughts, but letting them go on as they will and continuing to relate to them as sensations moving through the body. Not clinging or condemning the passing show of mind, but watching it as the comings and goings of the dance of life in the field of sensation.

Different Ways of Seeing Dyslexia

At one point I found a book called Smart but Feeling Dumb that helped me understand something of the workings of a brain that finds it difficult to learn in the “normal” manner. The author, Harold Levinson, had two dyslexic daughters and surmised it was an inner ear/cerebellum and eye disorder.

He spoke about many styles of dyslexia. Some dyslexics can’t read, others can’t spell. Many visualize, taking mental photos of whatever they need to read. Others memorize words but still have trouble correctly sounding them out. I had all of the above. I still can’t sound out words well no matter how much I break them into syllables.

Levinson helped me understand what was going on inside me. He gave me great confidence when he wrote it was my brain, not my mind that needed tilting. He made me laugh just when I needed it.

He showed me I wasn’t stupid, but actually a jigsaw puzzle master who had taught myself to piece together what was being seen and heard, and then to fit it together in a recognizable manner. If my grade school teachers had told me this, it might have saved me incarnations of shame and confusion.

I never met another dyslexic person until I met the well-known physician/healer/writer Gerald Jampolsky, the fellow who started the centers for Attitudinal Healing. He didn’t find out he was dyslexic until his second year of medical school. What a beautiful person he is. Sometimes I wonder if having undiagnosed learning disabilities doesn’t separate the heart from the mind and leave even some of the smartest people feeling lost and irretrievable.

Calming the Mind

When I started my first practice, mantra, I learned to steady myself and watch how the intentional repetition of a phrase began to quiet down the unintentional, compulsive repetitions of my mind. The practice provided me spaces between thoughts from which to simply watch and slow the habitual tendency to react rather than respond.

As time went on and I learned to meditate, I was able to see what was going on in the passing show on the screen of consciousness. I saw I didn’t have to jump at every stimulus and could let what was superfluous just sail by, which naturally lessened the anxiety in my interactions.

Anxiety and fear arise with neurological disorders, but this doesn’t mean that you are “a dysfunctional being.” It just means you have specific work to do on yourself that will help you adjust to your surroundings.

It’s all too easy to slap labels on ourselves, to judge ourselves to be outsiders unfit for normal society. (Not that being an outsider is a bad thing when that becomes a conscious choice to move beyond the chatter and clatter of the common milieu.) Most conditions are at least somewhat workable with a patient cultivation of concentration and a nonjudgmental effort to liberate oneself.

In saying, “Judge not, lest you be judged,” Jesus was slipping a rare secret under our cell door, revealing that the nature of the judging-mind doesn’t know us from the person next to us and treats all with equal mercilessness.

It takes awhile to calm the mind and allow the heart to feel safe, to come into its own, like coming to the surface, but who has anything better to do?

Making Love the Primary Means of Communication

When I started living with Stephen, the pain was diminishing as I came to see with considerable relief that my dreaded word scramble small talk was a conduit for the heart, actually a means of communicating love. The tension of resistance to boredom and self-righteousness responded to the hardening and softening of the belly and the letting go of separation. Kind of a “hold and release” experience where we find ourselves lost and let go, calling ourselves home. My long-conditioned speech patterns softened as love became the primary means of communication. Acceptance bonds.

My awareness practices changed much of this in a most wonderful manner. Of course, I still have the personality I was dealt, with all the twists and turns of organic brain issues, but practice has given me the insight and method to relate “to” states of mind and not “from” them. I often experience myself watching “anxiety” now rather than just being “anxious.”

I am considerably freer than in my youth, with more room to live in and, thankfully, greater access to my heart. I think people who in my youth once shunned me as weird might now just find me a bit eccentric.

The Flowering of the Heart

I started working at a local hospital and nursing home with patients others did not care to attend to. The elderly patients who were so sick and so alone were lined up each morning against the walls in the hallways, longing to be touched, longing for someone who somehow reminded them of a long-lost loved one. The appreciation I got from them gave me a sense of being able to help, to do some good as perhaps nowhere else. My heart discovered the hope that borders on faith and trust that seamlessly enters the future with an answer that brings us all back into the human race.

It turned out that those in a coma were not “gone” but just hanging out on the mezzanine. They were not on the second floor, but just watching from above, so to speak. It is difficult for me to find the right language to describe this, but a few of the people who recovered from their comas would occasionally, with considerable gratitude, thank me for my support “while we were together in there.”

Like many, I left my parents’ home looking for my true family, the family that trusts and supports the heart’s work and remains present for the mind’s travail. I needed to learn how to touch, how to feel, and how to laugh and play. Most certainly I needed to connect with others, if not to be loved as I wished, then certainly to love and offer what I could that served others—whatever was of use from what I called my weirdness.

©2012 & 2015 by Ondrea Levine and Stephen Levine. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission of the publisher, Weiser Books,

an imprint of Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC. www.redwheelweiser.com

Article Source:

The Healing I Took Birth For: Practicing the Art of Compassion

The Healing I Took Birth For: Practicing the Art of Compassion

by Ondrea Levine (as told to Stephen Levine).

Click here for more info and/or to order this book.

Watch a video (and book trailer): The Healing I Took Birth For (with Ondrea & Stephen Levine)

About the Author

Ondrea Levine and Stephen Levine are close collaborators in teaching, in practice, in life. Together they are the authors of more than eight books, some of which bear Stephen's name only as author, but all of which Ondrea had a hand in. Together they are best known for their work on death and dying. Visit them at www.levinetalks.com

Ondrea Levine and Stephen Levine are close collaborators in teaching, in practice, in life. Together they are the authors of more than eight books, some of which bear Stephen's name only as author, but all of which Ondrea had a hand in. Together they are best known for their work on death and dying. Visit them at www.levinetalks.com