Image by Prawny

There is a conflict in early twenty-first century New Thought. Some seekers want a New Thought that emphasizes personal attainment and ambition. Others believe that New Thought’s focus should be on social justice—they view the think-and-grow-rich approach as narrow, unspiritual, or outdated.

The 1910 classic The Science of Getting Rich by mind-power pioneer and social activist Wallace D. Wattles (1860–1911) points the way out of this conflict. Wattles’s message is distinctly relevant for a contemporary New Thought culture that is divided between social justice and personal achievement. The author and Progressive Era reformer demonstrated how these two priorities are really one.

A socialist, a Quaker, and an early theorist of mind-positive metaphysics, Wattles taught that the true aim of enrichment is not accumulation of personal resources alone, but also the establishment of a more equitable world, one of shared abundance and possibility. He believed that combining mind-power mechanics with an ardent dedication to self-improvement—while rejecting a narrowly competitive, me-first ethos—makes you part of an interlinking chain that leads to a more prosperous dynamic for everyone.

Wattles’s slender guidebook The Science of Getting Rich remained obscure in mainstream culture until about 2007. Around that time, The Science of Getting Rich became known as a key source behind Rhonda Byrne’s The Secret. The century-old book began hitting bestseller lists. I published a paperback edition myself that hit number one on the Bloomberg Businessweek list. My 2016 audio condensation reached number two on iTunes.

Competition Is An Outmoded Idea

What many of Wattles’s twenty-first-century readers miss, however, is his dedication to the ethic of cooperative advancement above competition and his belief that competition itself is an outmoded idea, due to be supplanted once humanity discovers the ever-renewing creative capacities of the mind. As none but the most perceptive readers could detect, Wattles combined his mind metaphysics with a dollop of Marxist language. His outlook was idealistic—perhaps extravagant—but he attempted to live up to it.

A onetime Methodist minister, Wattles lost his northern Indiana pulpit when he refused collection-basket offerings from congregants who owned sweatshops. He twice ran for office on the ticket of fellow Hoosier Eugene V. Debs’s Socialist Party, first for Congress and again as a close second for mayor of Elwood, Indiana.

At the time of his death in 1911, he and his daughter, Florence (1888–1947)—a powerful socialist orator in her own right and later the publicity director at publisher E. P. Dutton—were laying the groundwork for a new mayoral run, cut short when he died of tuberculosis at age fifty while traveling to Tennessee.

Florence wrote to Eugene Debs’s brother, Theodore, on January 30, 1935. Addressing him as “Dear Comrade,” she lovingly recalled her father as “a remarkable personality, and a beautiful spirit, which, to me, at least, has never died.”

Was Wattles’s Vision Utopian?

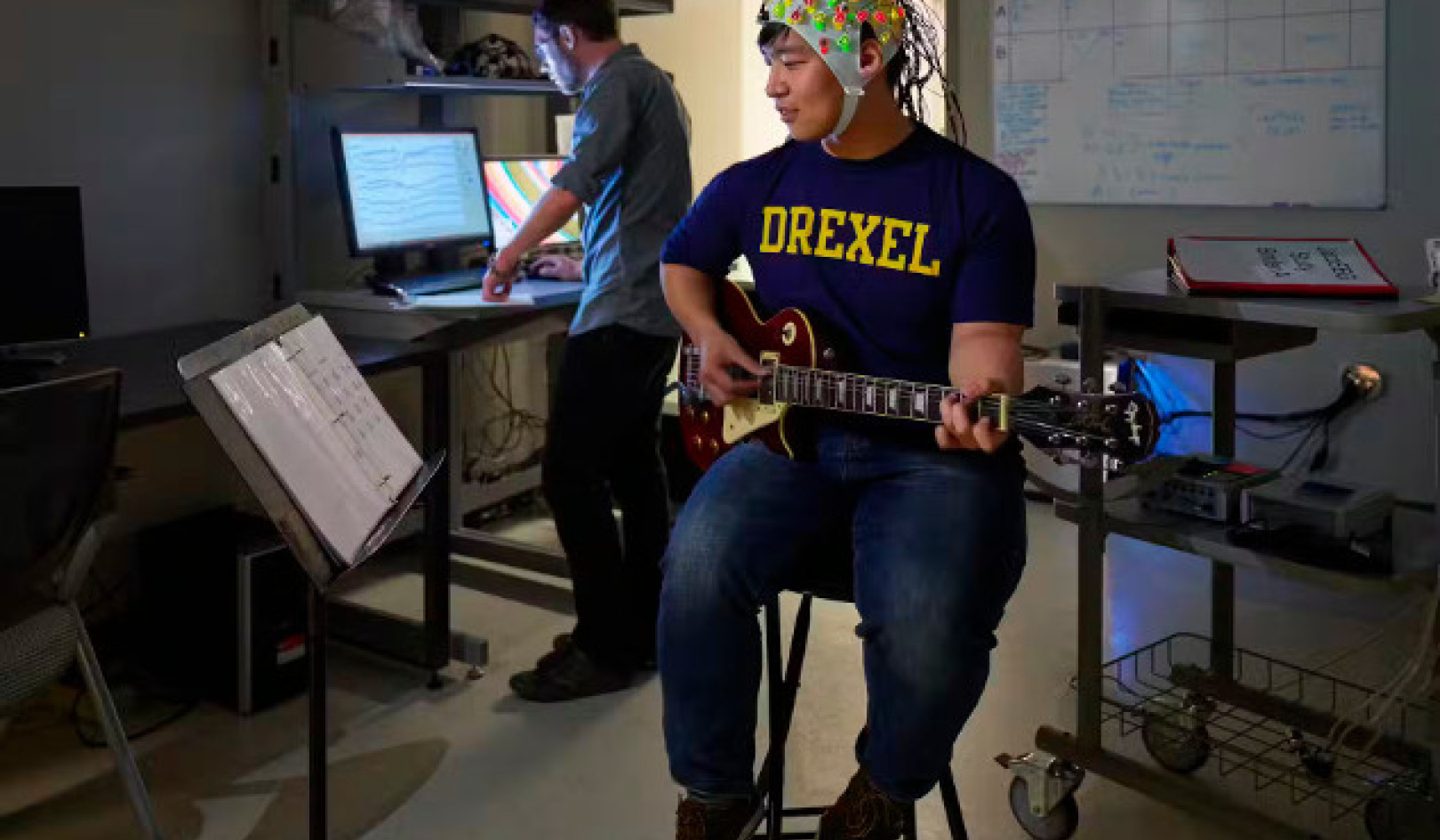

Was Wattles’s vision of New Thought metaphysics and social reform really so utopian? We live in an age at which he would have marveled—yet also recognized: physicians perform successful placebo surgeries, and demonstrate the placebo response in weight loss, eyesight, and even in instances where placebos are transparently administered; in the field called neuroplasticity, brain scans reveal that neural pathways are “rewired” by thought patterns—a biologic fact of mind over matter; quantum physics experiments, as will later be seen, pose extraordinary questions about the intersection between thought and object; and serious ESP experiments repeatedly demonstrate the nonphysical conveyance of information in laboratory settings.

Wattles’s mission, now more than a century old, was to ask whether these abilities, only hinted at in the science of his day, could be personally applied and tested on the material and social scales of life.

He did not live to see the influence of his book. But his calm certainty and confident yet gentle tone suggest that he felt assured of his ideas. Like every sound thinker, Wattles left us not with a doctrine, but with articles of experimentation. The finest thing you can do to honor the memory of this good man—and to advance on your own path in life—is to heed his advice: Go and experiment with the capacities of your mind. Go and try. And if you experience results, do as he did: tell the people.

A New Vision of Mind Power

We are at a propitious moment to reexamine Wattles. The New Thought movement, as noted, is conflicted between urges to “change the world” or “be on top of the world.” This tension may be the chrysalis from which a new approach emerges.

Here is a starting point: In her 2016 blog article Why the Self-Help Industry Isn’t Changing the World, spiritual counselor and writer Andréa Ranae raised excellent points about why today’s self-help culture deals poorly with social questions. Like Ranae, I have had the experience of witnessing a tragedy in the world only to log onto social media to find the usual population of motivational gurus prattling away like nothing has happened, offering the standard you-can-do-it nostrums. Or, in awkwardly acknowledging a tragic event, they might show an image like a cake with a candle blown out, or some similarly cloying gesture. Like Ranae, I’ve never believed that the New Thought and self-help movements should stand aloof from human events. (e.g., see my “What Does New Thought Say about War?” post at HarvBishop.com.)

But Ranae argues a deeper point, which is that many of the problems people bring to her as a spiritual counselor are actually symptoms of an unjust world; it feels to her like she’s avoiding the point if she treats the personal symptom and not the larger cause.

I honor that point—but I approach these matters somewhat differently. Human nature, in its complexities, is twisted into knots, some of them resulting from outer circumstances, and some from within ourselves. That will always be the case.

I do not want to see an overly politicized New Thought in the twenty-first century. I do not want a New Thought that is closed off to people who are, in fact, suspicious of “social action,” which can quickly devolve into posturing, vague pronouncements, and inertia. People harbor vastly—and justly—different ideas of social polity. Indeed, a poorly defined social-justice model in New Thought can actually deemphasize the pursuit of individual attainment, which is historically vital to New Thought’s appeal.

I must also add that, in my experience, some of the loudest proponents of social justice in our spiritual communities cannot be counted on to water a houseplant. If you want social justice, I often tell people, begin with the ethic of keeping your word and excelling at the basics of organization and planning. Start there—and if you perform well at those things, expand your vision. You cannot “fix” things that affect others unless you can first care for the things that are your own.

Must You Choose Between A Nice Car and “Awareness”?

In my 2014 book One Simple Idea, I wrote critically of success guru Napoleon Hill. I saw the Think and Grow Rich author as someone who moved the dial away from social justice in the American metaphysical tradition. But, in retrospect, I was wrong. It’s not that my criticism of Hill was off target; the writer made pronouncements and did things to which I object. But Hill’s greatness as a metaphysician and motivational thinker was to frame a truly workable program of ethical, individual success. He owed no apology for that.

One online writer recently wrote a bellicose, drawn-out article impugning Hill’s character. But the one historically significant thing about Hill is his work, and you cannot evaluate the man absent that—any more than the sensationalistic biographer Albert Goldman could capture the characters of John Lennon or Elvis Presley, two of his subjects, without understanding them as artists. Hill’s success program has earned its posterity, which I know from personal experience.

New Thought at its best and most infectious celebrates the primacy of the individual. Seen in a certain light, the mystical teacher Neville Goddard, the New Thought figure whom I most admire, was a kind of spiritualized objectivist. Or perhaps I could say that Ayn Rand, the founder of philosophical Objectivism, and an ardent atheist, was a secularized Neville. Neville and Rand each espoused a form of extremist self-responsibility. Objective reality, each taught, is a fact of life.

The motivated person must select among the possibilities and circumstances of reality. In their view, the individual is solely responsible, ultimately, for what he does with his choices. Rand saw this selection as the exercise of personal will and rational judgment; Neville saw it as vested in the creative instrumentalities of your imagination. But both espoused the same principle: the world that you occupy is your own obligation.

Is there a dichotomy between Neville’s radical individualism and the communal vision of Wattles? Not for me. I’m skeptical toward language such as inner/outer, essence/ego, spiritual/material, which buzzes around many of our alternative spiritual communities. Not only do opposites attract, but paradoxes complete. It is in the nature of life.

There are no neat lines of division in the territory of truth. Neville’s vision of individual excellence, and Wattles’s ideal of community enrichment are inextricably bound because New Thought—unlike secular Objectivism and varying forms of ceremonial magick or Thelemic philosophy—functions along the lines of Scriptural ethics.

New Thought does not countenance an exclusivist society. It promulgates a radically karmic ethos, in which the thoughts and actions enacted toward others simultaneously play out toward the self; doing unto others is doing unto self—the part and the whole are inseparable.

Those of us involved with New Thought are, in fact, always striving to see life as “one thing.” That one thing—call it the Creative Power or Higher Mind in which we all function—can expand in infinite directions. Must a seeker choose between a nice car and “awareness”? Must I choose between Wallace D. Wattles and Neville? Both were bold, beautiful, and right in many ways; both had a vision of ultimate freedom—of the creative individual determining rather than bending to circumstance.

Improving The Intellectual Tenor Of New Thought

Rather than propose a political program for New Thought, I instead want to strike at the blithe, sometimes childish tone that pervades much of its culture. Within churches, meetings, and discussion groups, people who think seriously about current events or ethical problems are sometimes regarded as missing the proper spirit. Yet thoughtful adults are not supposed to be Mr. Roarke saying, “Smiles everyone, smiles!” (Young people, work with me . . .) Indeed, some New Thoughters even express boredom with discussions of world issues or are grievously uninformed about such things. I was once making a point to a New Thought minister, and he gestured with his hand from the base of his neck to the top of his skull and said, “That sounds very here up.” I was being too intellectual, he felt. Such prohibitions do not foster a well-rounded movement.

Rather than venture political agendas, we must improve the intellectual tenor of New Thought—and avoid leaning on catechism when topics of tragedy or injustice arise. A familiar New Thought refrain is that someone who has experienced tragedy, either on a personal or mass scale, was somehow thinking in comportment with the grievous event. That is indefensible. We are, in fact, always thinking about different needs and possibilities, shifting among competing thoughts and interests; the key factor in whether a thought becomes determinative, as seen in psychical and placebo studies as well as in the testimony of individual seekers, is when emotional force and sublime focus combine in a single thought. How can a swath of people, whether in a country or as pedestrians at an event, be classified as forming a discernable mental whole?

I’m not saying that there isn’t mass psychology. Following traumatic events, and during moments of heightened crowd stimulation (such as hearing a powerful speech), a kind of herd psychology or groupthink can certainly take hold. But preceding such events, human thoughts are frenetic and unruly, often as busied and individualized as movements on a crowded street. I see no evidence of a group will to suffer.

Taking Seriously Both The Spiritual and Public Dimensions Of Life

Just as there is no sole cause, nor a single mental law, behind tragedies, there is no one answer when analyzing politics or current events. But what no serious spiritual movement can sustain is having no answer or no response. Or no discussion. Or no perspective. I would rather enter a roomful of people who civilly disagree on problematic issues than are blissfully indifferent, or who run from discussion as though from contagion, which is the default to which some New Thoughters have wed themselves.

This kind of studied indifference is the problem that Andréa Ranae is putting her finger on. It is a serious one. Yet historically it was not a problem for pioneers like Wallace Wattles or his publisher, Elizabeth Towne, a leading New Thought voice and suffragist activist. In 1926, Towne was elected the first female alderman in Holyoke, Massachusetts. Two years later she mounted an unsuccessful independent bid for mayor.

Progressive Era pioneers of New Thought like Towne, Wattles, Helen Wilmans, Ralph Waldo Trine, and many of their contemporaries, were socially and intellectually well rounded. They took seriously both the spiritual and public dimensions of life. Their expansive outlooks were a natural expression of their driving curiosity and engagement with the world. If we can foster a better, fuller intellectual culture within New Thought (which is one of the aims of this book), I think the poles of social action and personal betterment would naturally converge.

A coalescing of interests does not mean that New Thoughters will agree on social issues, or vote the same. It means that New Thought values and methods will shine the way for each seeker, whatever his values or circumstances, to shape his life—and the world—in accordance with his highest self.

©2018 by Mitch Horowitz. All Rights Reserved.

Reprinted with permission of Inner Traditions Intl.

www.InnerTraditions.com

Article Source

The Miracle Club: How Thoughts Become Reality

by Mitch Horowitz

Laying out a specific path to manifest your deepest desires, from wealth and love to happiness and security, Mitch Horowitz provides focused exercises and concrete tools for change and looks at ways to get more out of prayer, affirmation, and visualization. He also provides the first serious reconsideration of New Thought philosophy since the death of William James in 1910. He includes crucial insights and effective methods from the movement’s leaders such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Napoleon Hill, Neville Goddard, William James, Andrew Jackson Davis, Wallace D. Wattles, and many others. Defining a miracle as “circumstances or events that surpass all conventional or natural expectation,” the author invites you to join him in pursuing miracles and achieve power over your own life.

Laying out a specific path to manifest your deepest desires, from wealth and love to happiness and security, Mitch Horowitz provides focused exercises and concrete tools for change and looks at ways to get more out of prayer, affirmation, and visualization. He also provides the first serious reconsideration of New Thought philosophy since the death of William James in 1910. He includes crucial insights and effective methods from the movement’s leaders such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Napoleon Hill, Neville Goddard, William James, Andrew Jackson Davis, Wallace D. Wattles, and many others. Defining a miracle as “circumstances or events that surpass all conventional or natural expectation,” the author invites you to join him in pursuing miracles and achieve power over your own life.

Click here for more info and/or to order this paperback book and/or download the Kindle edition.

More Books by this Author

About the Author

Mitch Horowitz is a PEN Award-winning historian, longtime publishing executive, and a leading New Thought commentator with bylines in The New York Times, Time, Politico, Salon, and The Wall Street Journal and media appearances on Dateline NBC, CBS Sunday Morning, All Things Considered, and Coast to Coast AM. He is the author of several books, including Occult America and One Simple Idea. For more info, visit: http://www.www.MitchHorowitz.com

Mitch Horowitz is a PEN Award-winning historian, longtime publishing executive, and a leading New Thought commentator with bylines in The New York Times, Time, Politico, Salon, and The Wall Street Journal and media appearances on Dateline NBC, CBS Sunday Morning, All Things Considered, and Coast to Coast AM. He is the author of several books, including Occult America and One Simple Idea. For more info, visit: http://www.www.MitchHorowitz.com